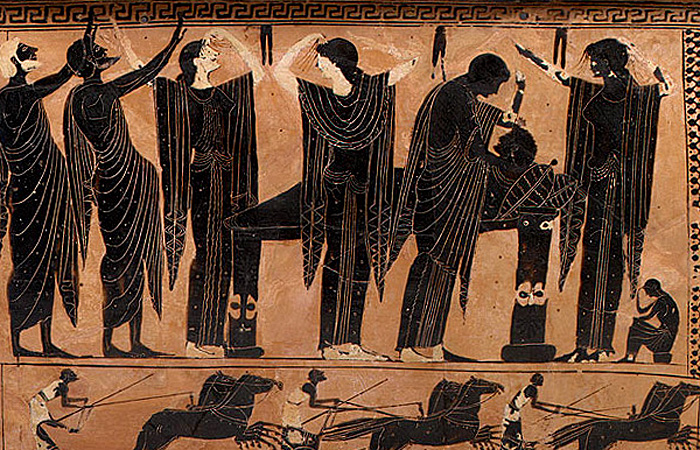

Illustration (detail) above: Decorative urn, Greece, 520 B.C.

Over time, sedentary pre-historic societies formed villages that, if successful, grew into towns and then small cities. Complex societies were achieved as a result of trade between cultures that came overland on caravans or along rivers where boats carrying cargo could reach farther inland. Coastal settlements, where the sea provided even greater access to shipping, became nodes of major commerce. Successful trade helped to form dominant military and political powers on the Greek and Italian peninsulas and the islands of the Aegean Sea. Trade routes were established to the wider Mediterranean, allowing influences to mingle and spread. The techniques of art and craft became widely understood and practiced.

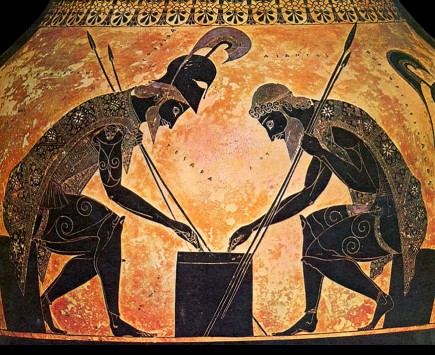

Exekias, decorative urn, Greece, ca.530 B.C.

Art flourished to honor gods and goddesses, royalty, military and political leaders, and cultural heroes. Illustrations of festivals, historic events, passages from literature and mythology, funeral scenes, and sporting competitions were painted onto ceremonial vessels. The Greek potter Exekias made decorative containers (amphora) painted with figure-scenes. One depicts Achilles and Ajax, the two greatest Greek warriors, playing a table game during a break in a siege. In 560 B.C. a Spartan potter illustrated the inside of a flat bowl with a scene of a King arguing with his steward while overseeing the weighing of a commodity. It shows a foreman giving orders to the men loading the scales and workers taking and stacking the bundles after they are weighed. The figure of the King is larger than other men, indicating his prominence, and the scene is both an illustration of events taking place in ordinary life and a tribute to the King’s wisdom and authority.

Decorative bowl, Sparta, ca.560 B.C.

As vivid as these pottery representations are, and as much as they tell about beliefs, rituals, daily lives, and entertainment of the Greeks, they were not considered to be a major art form in their time. Wall and panel painting were the major arts, but little of that remains. The homes of the wealthiest Romans featured wall paintings that showed family life, portraits, and scenes from literature. Floors might be covered with pictorial mosaics. Roman Christians decorated their secret places of worship with illustrations from scripture. Roman architecture also utilized illustration—carved in stone as an important feature of buildings and monuments. Trajan’s Column in Rome, for example, has a spiraling, sequential illustration carved into it depicting a narrative from bottom to top that honors that Emperor’s victory over a rival state.

Roman wall painting, The Odyssey, "Laestrygonians hurling rocks at the fleet of Odysseus (Ulysses)"

Early Christian catacomb painting, ca.300s A.D.

Trajan's Column, Rome, 113 A.D.

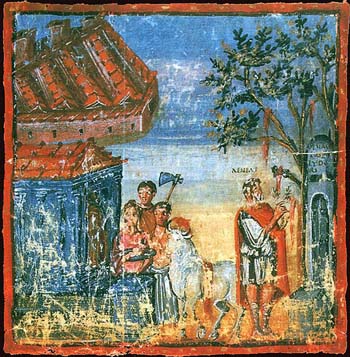

Romans were among the first to create bound books made of vellum pages (animal skin) to record literature, poetry, mythology, and matters of science, medicine, and government. Some books were illustrated using full-bodied pigments (the illustrated Vatican Virgil)—an approach made possible because vellum pages were relatively rigid vs. papyrus scrolls, which tended to be painted with thinner watercolor pigment and natural dyes because, in time, thicker paint would crack from rolling and unrolling.

Vatican Virgil, Rome, ca.400s A.D.