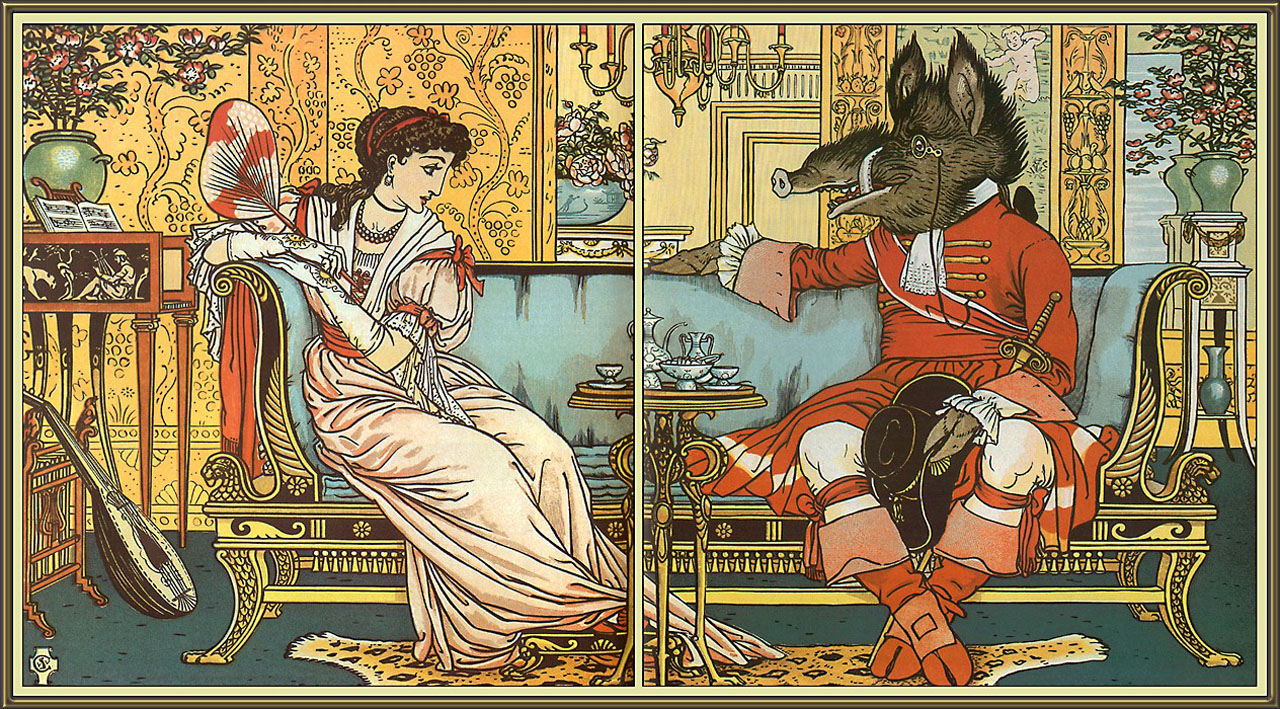

Illustration (detail) above: Walter Crane, Beauty and the Beast, 1874

In the second half of the 19th Century, printing technology in the United States was advancing to meet the needs of a population expanding from coast to coast. Faster printing presses and the construction and connection of the railroad system and postal service made the manufacture and distribution of books, magazines, and newspapers more efficient, and the nation was able to read about and respond to current events more quickly than ever before. Illustration was important to publications like Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and Harper’s Weekly. Artists, salaried as on-site reporters, sketched events as they were taking place, while freelancers were paid to do political cartoons, allegorical pictures, and story illustrations. In order for the artwork to be printed, the original artwork—generally done in pen and ink— had to be interpreted by wood engravers who created the printing blocks that would go on the presses.

Winslow Homer, engraving made from reportage drawing, "Surgeons at the Rear," 1862

Harper and Brothers publishers, already successful with its books and illustrated weekly newspaper, created a monthly magazine and formed a staff of in-house artists to make pen drawings on a wide range of subjects and narrative fiction. These illustrators of the 1870s and 1880s were among the finest in the world, each with his own specialty: Thomas Nast for political cartoons, Thur de Thulstrup for history and horses, Howard Pyle for Americana, Edwin Austin Abbey for all things costumed or English, William A. Rogers for urban scenes, A. B. Frost for rural subjects and humor, and Frederic Remington for the western frontier. This great collection of talent led American publishing to finally rival the quality of European illustrated journals.

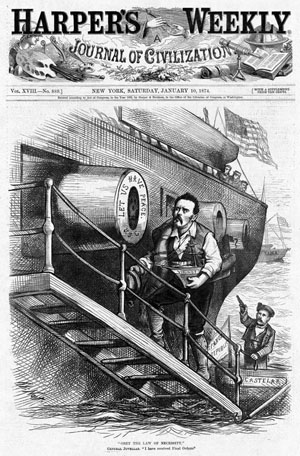

In the words of his biographer, “If Thomas Nast was merely a cartoonist, then Abraham Lincoln was merely a politician.” Followers of Nast’s political cartoons tripled the circulation of Harper’s Weekly. Political personalities that he satirized were weakened and usually dethroned, and every presidential candidate that he supported was elected. He expressed his opinion on every important social and political issue of his time, created the elephant and donkey symbols for the Republican and Democratic parties and gave America its now familiar portrayals of Uncle Sam and Santa Claus.

Thomas Nast, cover illustration, Harper's Weekly, 1874

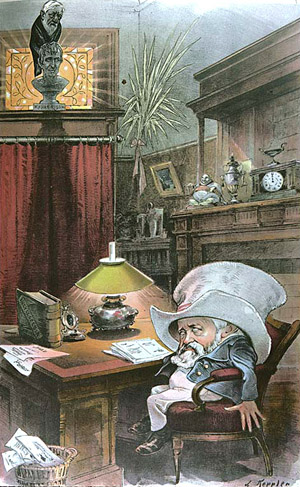

English artist/illustrators associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood—Dante Gabriel Rosetti, Edward Burne-Jones, Frederick Sandys, A.B. Houghton, and others—created drawings for books and literary journals. Typically, these would be translated by wood engravers or wood block cutters. The Dalziel Brothers were the finest engraving craftsmen of their time and their interpretations of artists' pen work was said to actually improve the picture's quality. The English were the first to adapt Japanese colored wood block printing techniques to book production. Edmund Evans, a former engraver, designed a method of printing illustrations in six colors and employed the talents of Walter Crane, Randolph Caldecott, and Kate Greenaway. Near the end of the century, the English illustrator Aubrey Beardsley was creating elegant and decadent work which was also, in part, influenced by Japanese graphic art. In France, the commercial posters of Czech artist Alphonse Mucha were the epitome of Art Nouveau illustration style. Art was drawn onto multiple stone lithographic plates representing particular colors, and resulted in a full-color effect. Color lithography, also called "chromolithography," was being used to produce advertising posters, business cards, and greeting cards and also for magazine covers and center pages (Joseph Keppler). Towards the end of the century, photoengraving allowed artists' original line art to be exactly reproduced without having to be interpreted through hand engraving. The halftone screening process was used to reproduce tonal paintings and photographs.

Arthur Boyd Houghton, book illustration (engraved by the Dalziel Bros.), 1868

Kate Greenaway, watercolor illustration, 1879

Aubrey Beardsley, book illustration in woodcut, from Salomé, a play by Oscar Wilde, 1894

Alphonse Mucha, lithographic print, "The Arts: Poetry," 1898

Joseph Keppler, colored lithograph, "Nevermore" (President William Henry Harrison), Puck magazine, 1890

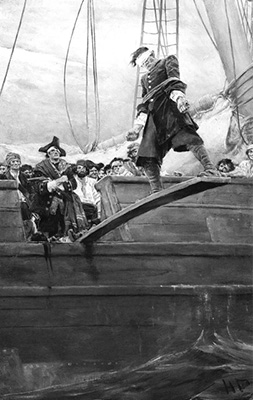

Howard Pyle became well-known for his illustrations in Harper’s Monthly Magazine and his illustrated children’s books. He told the story of the legendary Robin Hood in an illustrated novel and revealed the world of pirate lore to readers of his illustrated short stories. In the 1890s he decided that he wanted to teach what he had learned through experience. At the time there were no courses in any schools or colleges for studying illustration, so he offered his services to the Drexel Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and in 1896 began teaching there. In that first year he had five students of extraordinary talent—three women and two men: Violet Oakley, Elizabeth Shippen Green, Jessie Wilcox Smith, Maxfield Parrish, and Frank Schoonover. Pyle’s classes grew from year to year as his reputation as a teacher spread. He created a special summer course for his most promising students that was held in an old mill along the Brandywine River in the village of Chadd’s Ford, Pennsylvania, and in 1900 he opened his own, tuition-free school in Wilmington, Delaware. The training he provided produced a crop of confident and supremely skilled young artists whom Pyle personally shepherded into their first professional work. The narrative realism that Pyle and they practiced became the primary approach to illustration of the early 20th Century and would come to be called the “Brandywine Tradition.”

Howard Pyle, oil painting, "Walking the Plank," later engraved for Harper's Monthly Magazine, 1887

Howard Pyle, oil painting, The Flying Dutchman, 1900