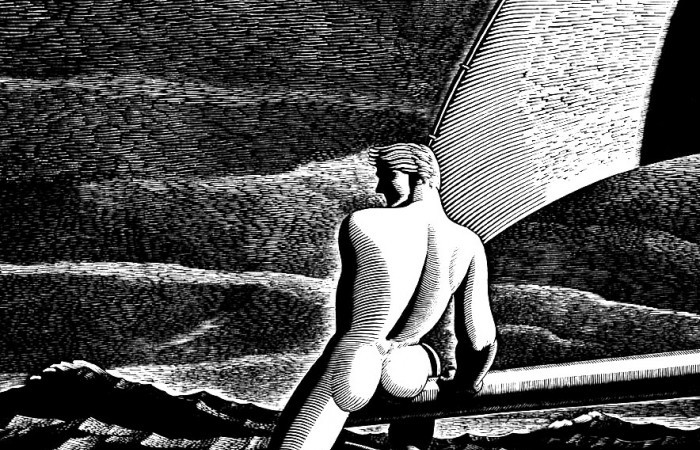

Illustration (detail) above: Rockwell Kent, 1931

The stock market crash of 1929 and the severe economic depression that followed naturally affected the publishing industry and the careers of illustrators. Book publishing suffered, with many publishers scaling back production and illustration commissions. To save costs in printing, the use of full-color illustrations inside books was limited. Instead, publishers commissioned line drawings from printmakers like Rockwell Kent and pen artists like Robert Lawson.

Robert Lawson, book illustration, Pilgrim's Progress, 1939

Magazines were always popular because of their relatively low cost and pass-along factor, but with reduced budgets there wasn’t much room for young illustration talent in the business. Established artists like J.C. Leyendecker and Dean Cornwell had plenty of assignments, though, because as always, their work—and their names—helped to sell publications. Traditional painters of narrative realism like Pruett Carter lent a classic, distinguished look to magazine fiction while contemporary water-colorists Mario Cooper, Floyd Davis, Harry Beckhoff, and cartoonist/illustrators like Wallace Morgan used stylizations that fit the times.

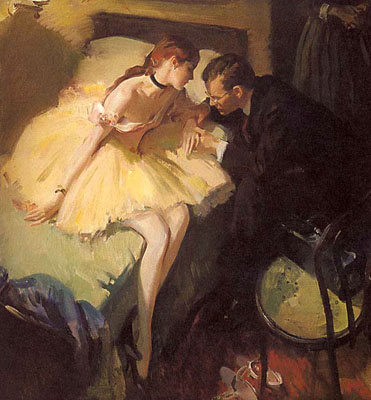

Pruett Carter, magazine illustration

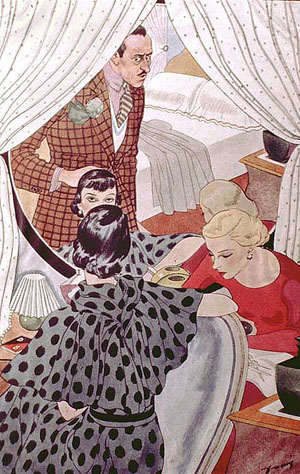

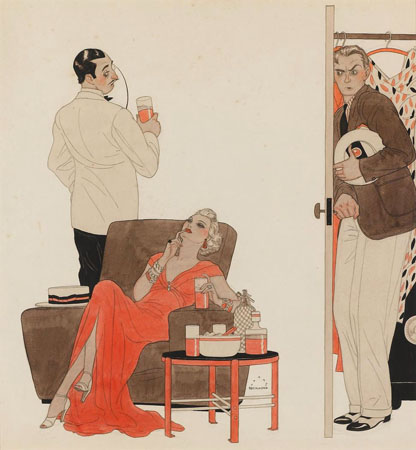

Mario Cooper, magazine illustration

Floyd Davis, magazine illustration

Wallace Morgan, magazine illustration

Harry Beckhoff, magazine illustration

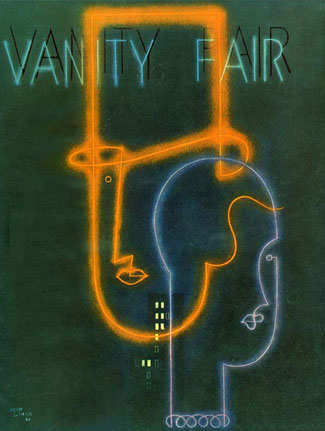

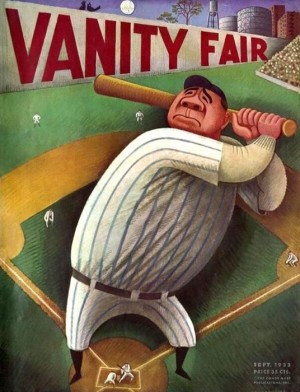

The illustration profession in the United States was also attracting international talent, including French-born poster artist Jean Carlu and Mexican caricaturist Miguel Covarrubias, who provided social and political satire on the pages of Vanity Fair magazine, which, in the 1930s was the primary literary and entertainment publication.

Jean Carlu, cover illustration, 1931

Miguel Covarrubias, cover illustration, Vanity Fair magazine, 1933

However, illustrated magazines were no longer America’s only form of entertainment. There was radio programming, which could be enjoyed for free, that presented drama, music, comedy, and world news. Even more importantly, the movie industry had grown substantially, with the number of films released increasing along with the number of theaters. Every town and city in America had a movie theater and the actors and actresses coming to life on the screens had great celebrity. Movie magazines, also called "screen" magazines, featured cover illustrations of beautiful actresses, and artists like Rolf Armstrong were extremely popular for creating portraits and "pin-ups." Hollywood presented entertainment and glamour on a grand scale that provided escape from the troubled times of the Great Depression.

Rolf Armstrong, cover portrait of actress Constance Bennett, 1931

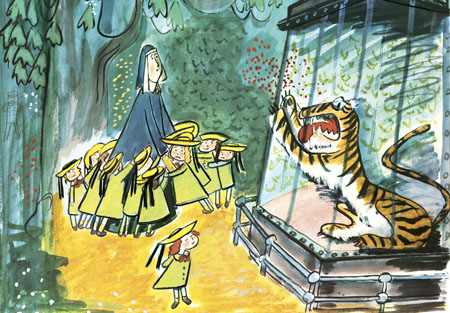

The ambitious Walt Disney turned his studio from making popular cartoon shorts like Steamboat Willie in 1928, the first sound cartoon, toward making full-length animated feature films, with Snow White beginning production in 1934 (released in 1937) and Pinocchio in 1936 (released in 1940). As inspiration for the animated drawings of Pinocchio, the Disney studio commissioned conceptual renderings by Swedish-American book illustrator Gustaf Tenggren. Tenggren also worked in a simplified second illustration style meant for children when he created art for the publishers of Little Golden Books (Poky Little Puppy). This decade was exceptional in terms of works for children. The Disney films and animated shorts (featuring Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, etc.) were not the only cartoon films being created in those years. Warner Bros. produced the "Merry Melodies" series and also "Looney Tunes," which gave the public Porky Pig, Daffy Duck, and Bugs Bunny. The list of classic children's picture books created by artist/writers in this decade is also extraordinary and includes the works of Jean de Brunhoff (Babar), Ludwig Bemelmans (Madeline), Hans Augusto Rey (Curious George), Dr. Seuss (Horton Hatches the Egg), and Virginia Lee Burton (Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel).

Gustaf Tenggren, concept art, Walt Disney's Pinnochio, 1936

Ludwig Bemelmans, Madeline, 1939