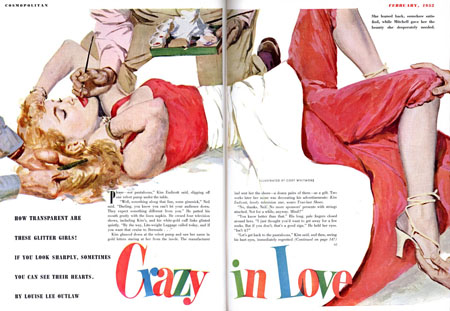

IIlustration (detail) above: Coby Whitmore

In the early 1950s, the Korean War, coming so soon after the end of the Second World War, found the news media well prepared for foreign reporting, and for the first time television cameras were used to record events as they happened. The Soviet Union had gained strength and as it absorbed what were called the "Eastern bloc" countries during and after World War II, the threat of the spread of Communism resulted in paranoia in the West. American senator Joseph McCarthy investigated those in the government who might ever have had a link to communist organizations or even had left-wing views. Homegrown anti-communist propaganda spread throughout American culture, with illustrated ads, posters, and feature articles warning of the "Red" menace and what it would do to the American way of life. The "Cold War" with the Soviet Union and Communist China began, and the arms race with its very real potential for atomic annihilation drove the country to fear for the future. In stressful times people seek diversions, and the entertainment industry provided movies produced in full-color and wide-screen formats, while the new medium of television was entering nearly every American home.

Cold War era corporate advertisement. Artist unknown.

In spite of the advent of television, the magazine publishing industry grew rapidly in the 1950s after a long lull through the Great Depression and war years. The Saturday Evening Post and Look had become the last remaining general interest family magazines and continued to publish articles of current events, short fiction, and features about family life and the arts. The largest consumer market in book and magazine publishing was women.

Coby Whitmore, Cosmopolitan magazine, 1952

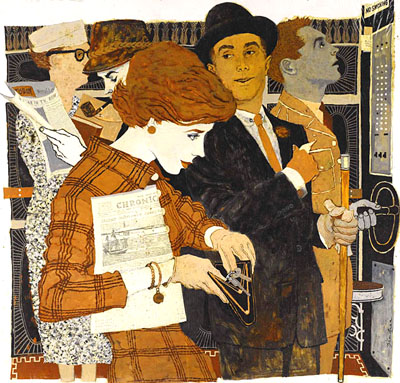

Cultural pressure to create the idealized American family had changed the image of self-sufficient, war-time women back to an earlier generation’s model of wife/mother/housekeeper (or single girl searching for romance and a husband) and all media reinforced this: radio, television, movies, and the publishing world. Stay-at-home mothers and even working women were a big part of the reading audience and the publishing industry provided them with gender specific magazines which used illustration. The term ”Seven Sisters” was applied to the dominant women’s magazines: Ladies Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, Woman’s Day, Women’s Home Companion, McCall’s, Redbook, and Cosmopolitan. These powerhouse publications were extensively illustrated and provided high-paying work to the top illustrators of the time, many of whom were working through agencies and professional sales representatives who brought in the work for a commission. Al Parker, Jon Whitcomb, Austin Briggs, Coby Whitmore, Joe De Mers, Bernard D’Andrea, and his wife Lorraine Fox were among the top-ranking illustrators of the day.

Bernard D'Andrea

Lorraine Fox

A range of publications for men were on the newsstands, too. There were special interest magazines for hunting, fishing, flying, mechanics, and science which all used illustration, as well as those which provided general interest men’s lifestyle content. Some featured photo layouts of beautiful women, like Hugh Hefner's Playboy magazine and Esquire magazine, both of which commissioned the best of illustration in each issue and strove to provide quality short fiction as well. Pulp short-story magazines and paperback pulp novels provided action, adventure, and science-fiction or fantasy stories and every issue had full-color cover illustrations. Two of the great pulp fiction artists of the 1940s and 1950s were Norman Saunders and Virgil Finlay.

Norman Saunders

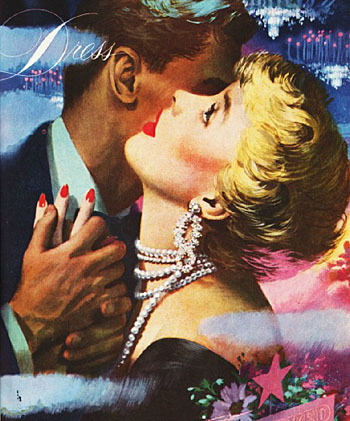

Throughout the publishing world there were plenty of assignments, even for young, entry level artists, but the way that illustrators were given assignments was beginning to change. Competition in manufacturing in a strengthening post-war, 1950s economy caused a surge in advertising (which increased revenues for newspaper and magazine publishers), and “Madison Avenue,” where the big New York ad agencies were located, became the nexus of a profession second only to Hollywood in its glamour. Advertising concept artists and storyboard artists could be employed in full-time, well paying jobs visualizing print ad campaigns and laying out commercials for the new medium of television. Magazines were competing furiously, and to maintain their already successful formulas, art direction was getting more specific—more and more, artists were being told what to illustrate and even how to illustrate it. The "boy/girl picture" and the "clinch," (Jon Whitcomb) were terms used to describe the formulaic embraces appearing in the women's magazines that most always showed a blonde female with dark-penciled brows, red lipstick, and a "peaches and cream" complexion who was paired with a tanned male, whose face was often half-hidden. If an artist objected to the specifics of the assignment, there were many others waiting in the wings to do the work.

Jon Whitcomb, magazine illustration

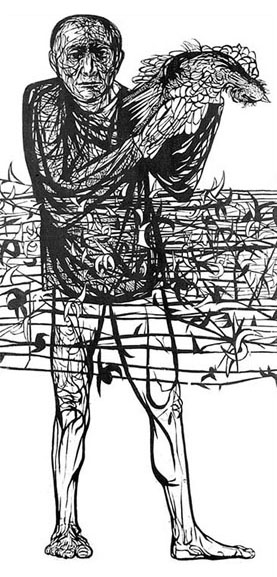

Predictably, creative art directors began to tire of the formulaic and stylized realism which dominated magazine illustration. Some began to turn to more spontaneous approaches for inspiration—like fashion illustration, poster art, and even fine art and printmaking by artists like Leonard Baskin and Ben Shaun.

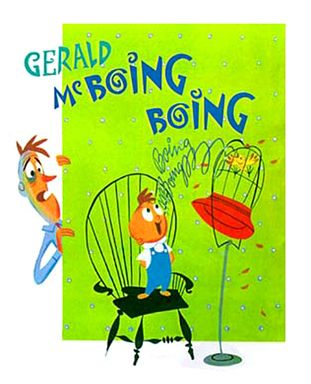

Just as families had gathered around their radios in the 1930s and 1940s, they now spent evenings at home, watching television together. People still kept their magazine subscriptions, but movies and television were now the dominant forms of entertainment. Animation was increasingly popular in movie theater shorts (UPA’s Gerald McBoing Boing) and on TV, and the playfulness of drawn characters in animation art influenced editorial and book illustrators. “Cartoony" drawing styles were beginning to be seen in many areas of illustration. U.S. ad agencies began using artists from Europe like André Francois whose simple, bold style for posters and advertising art was a refreshing change from American realism and inspired American ad agencies to consider looser approaches.

In the late 1950s, photography began to replace conventional, realistic illustration in advertising. More abstract approaches to illustration however, did not compete with what the camera could do and innovative art directors utilized illustrators with more playful styles as a way of attracting attention to ads or publications. It was clear that the second half of the 20th Century would bring a surge of creative stylizations.

Leonard Baskin, 1952

United Productions of America (UPA) animation art

André François, 1956