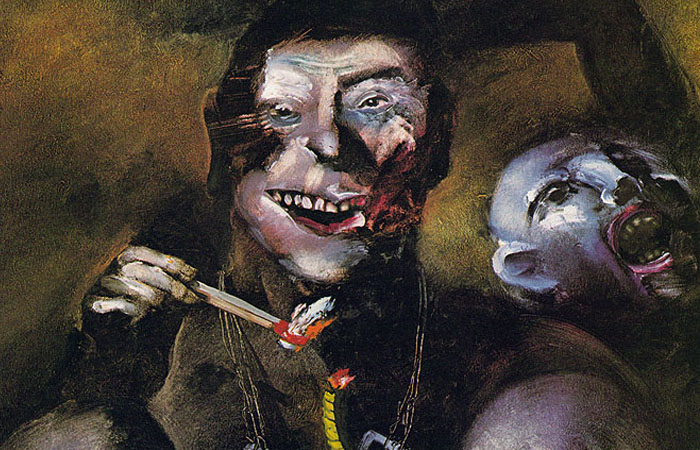

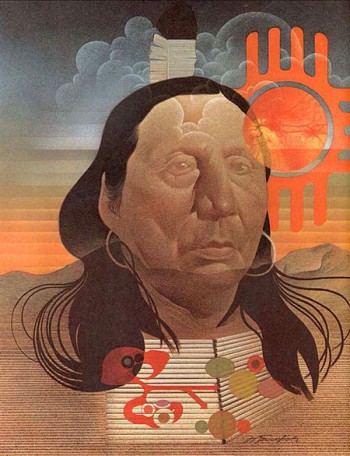

Illustration (detail) above: Marshall Arisman, magazine illustration, "Reagan and Latin America," 1984

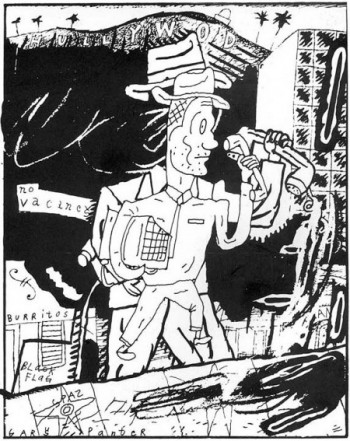

The 1980s were creative years in illustration. "Neo-Expressionist" artists like Marshall Arisman and Gary Panter shook the mildness out of magazine art with their scratched lines, splattered inks, jagged shapes, and implied violence. "The New Illustration" showed influences of punk rock attitude, while making social and cultural commentary. Crude or primitive drawing became more acceptable in the minds of some art directors, while most of the profession maintained the status quo of past decades.

Gary Panter

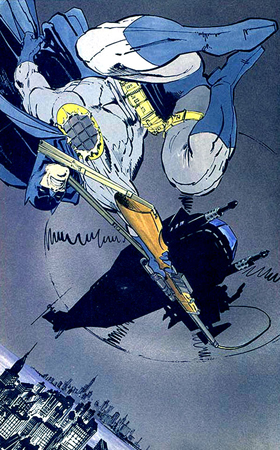

Gary Panter and other comics artists rose from the underground into the light of mainstream publishing as comics attracted a wider audience. The extended length comic narrative surged forward with the The Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller, a story that delved into the psychology of the most troubled of crime-fighting heroes, Batman, and led the way to other thoughtful and complex story-telling that would form the genre called the "graphic novel."

Frank Miller, graphic novel, The Dark Knight Returns, 1986

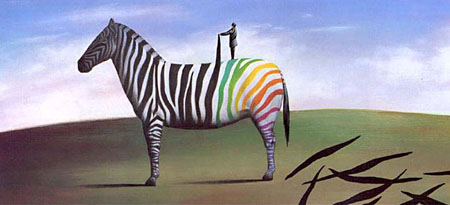

Beginning with the conceptual illustrations done for The New York Times in the 1970s, a symbolic and surrealistic illustration style became popular in the 1980s and 1990s in other areas of publishing. In advertising and marketing for businesses, in corporate annual reports, and in business and financial publications, concepts were being treated with solutions, which, although often creative, were of a common type. The businessman or woman, the office worker, and the investor were symbolized by a single generic figure interacting with a symbolic, concept-based environment that represented the company. The "corporate everyman" (or team of employees) was seen climbing ladders to attain goals, crossing half-built bridges to show perilous transitions, and facing many other metaphorical situations.

George Abe

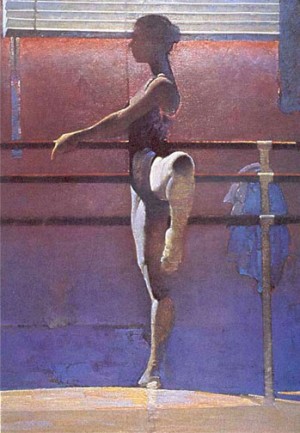

There were lucrative markets in the favored business world of Reagan-era economics. Artists like Mark English, Fred Otnes, Bernie Fuchs and Robert Heindel earned large fees for the paintings they produced for corporations, institutions, and advertising clients. And, if they chose to, they could also function as fine artists by creating self-authored works on subjects of their choice and selling them as art for corporate offices for very substantial sums. This, along with editorial and book illustration assignments, allowed this first rank of American illustrators to live an envied lifestyle and to serve as role models for both financial and artistic success.

Mark English

Robert Heindel

Children's book illustration continued to grow as a field in the 1980s and showed a wide range of styles and content. In a strong economy illustrators could conduct fully active careers solely on income from children's publishers. Trina Schart Hyman, Nancy Burkholm Eckert, Chris van Allsburg, Barry Moser, Alice and Martin Provensen, Susan Jeffers, Mercer Mayer, and Tommy dePaola were among the most successful ones. And in this decade, for the first time in history, there were picture books being created by African-Americans about the African-American experience. These include Leo Dillon, of the illustrator team Leo and Diane Dillon (Ashanti to Zulu), Jerry Pinkney (Tales of Uncle Remus), and John Steptoe (Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughters). Steptoe's career was cut short in 1989 when he died of the AIDS virus but Pinkney and the Dillons continue to create wonderful books today.

Leo and Diane Dillon, Ashanti to Zulu, 1977

Change was coming quickly in the illustration profession. For a hundred years, the art and business of illustration had been conducted in pretty much the same ways. The conventions of looking for work, getting a portfolio reviewed, promoting work, gaining commissions, and communicating with art directors were not much different for Howard Pyle than they were for Mark English. In this decade, when art school illustration programs were turning out young illustrators with brand new portfolios each spring, art directors were beginning to limit personal interviews. They came to prefer seeing artist's representatives who could bring samples by multiple artists and were professional sales people, rather than interacting with eager artists seeking input and advice. Agencies and publishers instituted "drop-off" policies, where portfolios were reviewed only on a particular day of the week, and often by someone other than the art director, such as a designated “art buyer,” junior designer, or assistant. With fewer opportunities to have their work reviewed personally, artists began seeking these "reps," who could more easily get into the doors of the agencies and publishers, while also seeking commissions, communicating assignments and sharing promotional costs. Artists without a rep were at a distinct disadvantage and in order to compete had to pay closer attention to marketing and promotion and spend more and more money on advertising. Occasional mailings to prospective clients had been the rule, but now illustrators were spending thousands of dollars for their own pages in new advertising annuals like American Showcase in the hope that art directors would see their work and get in touch. For the art directors, these annuals provided a huge menu of choices and became the primary way that artists or reps were selected. The most talented artists did well, and the less talented suffered discouraging losses and longer periods of downtime when commissions were scarce. The fax machine and new overnight delivery services all but replaced personal contact during the process of making an illustration, and artists communicated with their clients only by a voice on the telephone—if at all.

Then, in the mid-1980s, the greatest advance in communication technology since Gutenberg invented the printing press took place. The desktop computer was invented. With its revolutionary combination of software and hardware, it would completely alter the ways that designers worked and provided the promise of a dynamic new medium for illustrators.