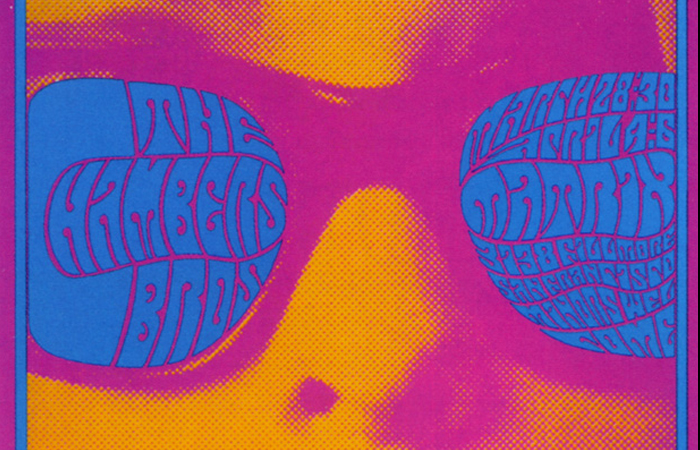

Illustration (detail) above: Victor Moscoso, concert poster, 1967

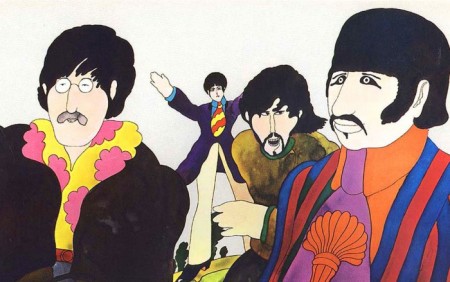

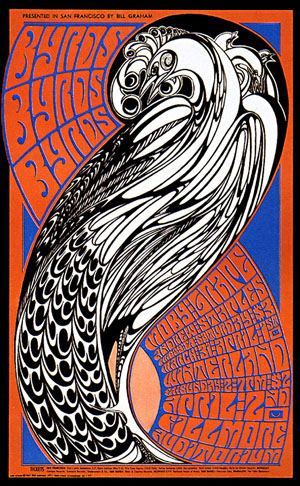

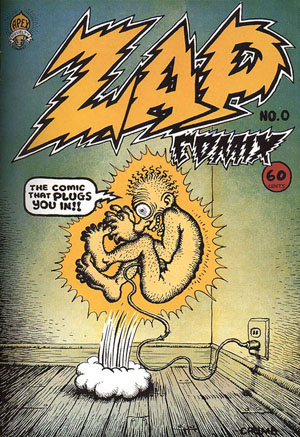

The first generation of children born after World War II, the “Baby-Boom” generation, was so large in number that socially and culturally, with each decade that passes, there has been pressure to follow its wants and needs. Teenagers of that generation rejected the popular music of their parents in favor of rock & roll or rhythm & blues with its inner city sounds and four- and five-part harmony singing groups. As the 1960s rolled in, new pop music from Europe, exemplified by the Beatles, immediately took hold in the United States. New fashions in clothing from London, new color palettes, and a “mod” approach to art and design swept through U.S. culture, affecting magazine design, graphics, posters, advertising, and illustration. In New York and San Francisco, music venues produced rock posters that challenged legibility in expressing the sounds and images associated with the psychedelic drug experience. Victor Moscoso, Wes Wilson, and others used Art Nouveau and Secession style influences combined with drawing, photography, and hand-lettering to create intensely visual poster experiences. Underground “comix” also began at this time in San Francisco and the drawings of Robert Crumb were seen as expressing the ennui of turned-on, tuned-out youth.

Heinz Edelman, animation drawing, The Yellow Submarine, 1968

Wes Wilson, concert poster, 1967

Robert Crumb, 1968

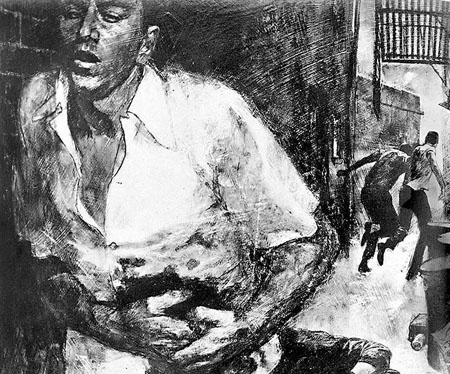

In the mainstream, established illustrators like Bob Peak continued to produce the same kinds of pictures that had been popular in the 1950s. There might be subtle distinctions between one artist and another in terms of style and content—but there was a growing trend in illustration towards each artist developing a distinctive personal style that would set him or her apart from all others. Increasing competition for illustration commissions came about when magazines started losing ground to television as the foremost entertainment medium. For artists to stand out, every imaginable kind of stylization was being created—from realism (Sandy Kossin) through abstraction (Saul Steinberg)—and every artist’s technique was developed with an eye towards originality.

Sanford Kossin

Saul Steinberg, 1964

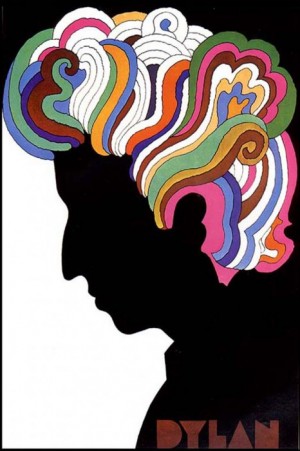

“Graphic design” became a distinct, creative discipline and modern advertising, publishing, and corporate designers were using typography, photography, and illustration in exciting, even daring new ways due to influences from post-war European modernists. These interconnected fields were represented in the trade magazines Graphis, Communication Arts, Art Direction, and Print which showcased the best work being produced in each area, providing influence and inspiration to their readers. Dual careers in illustration and design were possible—most clearly exemplified by the artist/designers of Push Pin Studios, Milton Glaser, and Seymour Chwast.

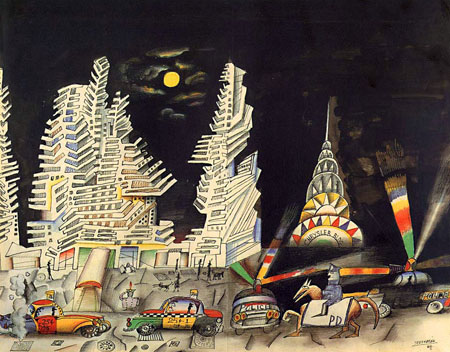

Milton Glaser, record album insert poster, 1966

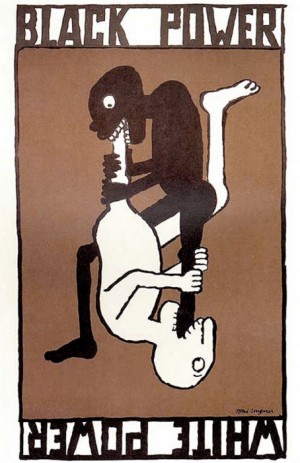

Ten years after the Korean War ended, a new conflict began in Vietnam. The draft was re-instituted, drawing the Baby Boom generation away from their education, careers, and families to serve in the military. Some artists who were in opposition to the war and other social policies (Tomi Ungerer and Paul Davis) chose to express their opinions through posters and in the “alternative media”—new magazines, newspapers, and radio stations—which arose with the goals of giving voice to dissent and invigorating the reshaping of a government seemingly deaf to its citizens. An “underground press” expressed opinions about the war and advocated the “sexual revolution,” women's liberation, and gay rights. In response to the lack of progress in the Civil Rights Movement, many African-Americans embraced the idea of “black pride” and some became radicalized. Left-wing and right-wing political lines were drawn, dividing the country while young Americans returned home in coffins. The protest movement became a many-faceted national phenomenon that would ultimately drive politicians to support ending the war and instituting social change.

Tomi Ungerer, poster, 1967

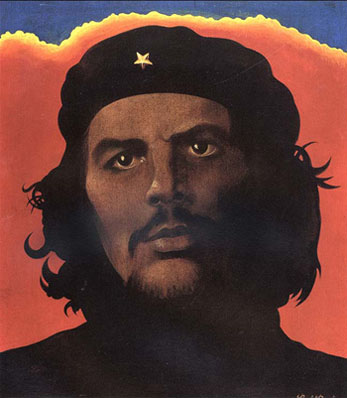

Paul Davis, magazine cover art, 1967