The Jazz Age (1919-1942) spanned over two decades of women challenging how they perceived themselves. They questioned their roles in the social world, their value in the workplace, and their position of power in romantic endeavors. Fueled by fashion and lifestyle magazines, the latest clothing styles were a vehicle for self-exploration leading to the flapper persona that many women adopted.

Defining the Flapper

The flapper was a woman who lived life on her own terms and valued self-governance above all. They rejected the definition of femininity created by the previous Victorian-era generation by wearing new fashions that were looser fitting for comfortability and to accentuate their natural figures. The flapper style of loose and linear dresses, bobbed hair, and heavily applied makeup was a “visual language” (Campbell Coyle, p. 110) first viewed as androgynous and then became the new form of femininity during the roaring 20s.

For the first time in the 20th century, during the Jazz Age (1919-1942), women were “taking up space” (Campbell Coyle, p.110). The new fashions allowed for flapper women to carry themselves well, expressing their emotions with a brash sense of humor. Flapper women went to social events without male chaperons,“They smoke, dance the Charleston, shout at football games, drive, drink, and read Freud.” (Campbell Coyle, p. 109). Another mannerism of the flapper was to apply makeup in public, especially with the invention of the makeup compact, consisting of a mirror and face powder.

Penrhyn Stanlaws, Cover for Collier’s Weekly, October 4, 1924, Acquired through the gift of Norman P. Rood, 2015, Delaware Art Museum Collection

Historically, particularly in Ancient Greece and neoclassical periods, women depicted staring into mirrors was a sign of vanity; now women were experimenting with pride and purposely calling attention to themselves with a newfound sense of confidence.

The Precursor, La Garçonne, and Fashion Illustration in France in the 1910s

Before there was the flapper in the United States, there was la garçonne in France in the 1910s. The term, la garçonne, comes from the French word for boy, le garçon, with the addition of the feminine article and feminine “ne” ending to the noun to refer to androgynous women.

La garçonne wore the latest styles from forward-thinking French designers such as Paul Poiret, Coco Chanel, and Elsa Schiaparelli. Chanel and Schiaparelli both designed sportswear collections made from jersey and knit fabrics, while Paul Poiret invented the first non-corseted dresses of the century. One of Poiret’s designs, the “lampshade design”, was a dress with a high waisted band at the top of the torso followed by fabric flowing down to the floor. These new causal and relaxed designs conveyed androgyny to reflect the new societal roles for women and provided sexual liberation.

The spread of these styles to the masses was through illustration in fashion and lifestyle magazines. The fashion and illustration industries merged forces when well-known illustrator, Paul Iribe, formed a business-relationship with designer, Paul Poiret. Iribe drew illustrations of Poiret’s work for the French fashion magazine Gazette du Bon Ton (1912-1925). Iribe used his “pochoir” method to depict the clothes, which called for creating a stencil for each layer of color applied by hand using gouache, an opaque watercolor paint. This method was inspired by Japanese wood-block printing and Japanese methods of layering stencils to create clean graphic lines. Japan’s new involvement in international trade with the West after the Edo Period (1603-1868) allowed for Europeans to adopt new artistic techniques. The spread of Japanese styles through trade and the pochoir method were the origin of clean and geometric Art Deco design. This technique and style dominated magazine illustration in the U.S. and Europe in the 1920s.

The Creation of the Flapper and the Historical Context that Allowed the Flapper to Thrive

Fashion was a means of “expressing and representing freedom” (Campbell Coyle, p.110) for la garçonne and then women in the United States, who sought a means of expression in a rapidly changing society. The roaring 20s began with the 19th amendment, granting white women the ability to vote, resulted in women seeking higher education and careers. Henry Ford had also invented affordable and accessible automobiles, making it possible for young people to move away from home to big cities. Margaret Sanger developed a contraceptive pill that allowed women to “assert control over their own bodies and sexuality” (Campbell Coyle, p.110). Another hallmark of the era was the Great Migration of African Americans from the rural south to the urban north in search of financial prosperity and to escape racial injustices. This led to jazz music performances at lively venues, fostering a nightlife culture for all young people. These historic happenings developed a young professional culture for women, calling for new clothing styles to be worn at work or to go out at night.

A common profession for a young woman of the 1920s was that of an illustrator. The economic boom after WWI led to a consumer culture fueled by companies publishing advertisements in mass-marketing magazines. French fashion houses recognized this opportunity to make profit and started to integrate their illustrations into American publications such as Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. This new French influence on American fashion inspired women to become illustrators and adapt new clothing styles. Women were already partaking in the workforce due to WWI drafts, but once granted this opportunity, many women found they did not want to lose this freedom. The popularity of magazines as a source of news, stories, lifestyle articles, and fashion led to a need for illustrators and “the business of drawing became a vocation...the circulation of the latest styles became an increasingly lucrative business.” (Goethe-Jones, 2019). The new role that magazines had in people’s lives, due to the adept female illustrators, enabled the 1920s and 30s era to be referred to as the “golden age” of fashion illustration. Female illustrators were able to “represent the texture, sheen, and even weight of the fabric” (Goethe-Jones, 2019) before the widespread usage of photography. During the late 1920s and early 1930s, photography became the preferred medium that “freed illustrators from the need to make an exact record of the clothing” (Goethe-Jones, 2019). Photography allowed female illustrators to become more creative with their designs, and many were known for their signature styles.

Women found a creative outlet in illustration and in fashion, where they were able to express their personalities to the ever-changing world they were living in. In a 1927 interview, well-revered American novelist, F. Scott Fitzgerald, once said “The girls I wrote about were not a type—they were a generation.” (Campbell Coyle, p. 111).

Highest Paid Woman Artist of the 20s and 30s, Helen Dryden, Designs Innovative Vogue Covers Depicting the Flapper

Helen Dryden (1882-1972) was a revered fashion illustrator known for being a trailblazer in Art Nouveau and Art Deco design in the United States. She drew on her knowledge of the French art world and took inspiration from her role models, Erté and Léon Bakst. Originally from Baltimore, MD, she decided to move to New York City to pursue fashion illustration in 1909. Her work was continually rejected from publications until she secured a contract with Vogue in 1910. Dryden illustrated Vogue covers and interior page illustrations for thirteen years. Her prosperous career with Vogue was the first of many accomplishments in design. Dryden truly understood the beauty of Deco design; she created costumes for Broadway productions, the interiors of Studebaker automobiles, textiles for New York department stores, and kitchenware. Dryden was coined “America’s First Lady of Design” in a June issue of Life magazine and was the highest paid female artist of the 1920s and 30s, making $100,000 a year.

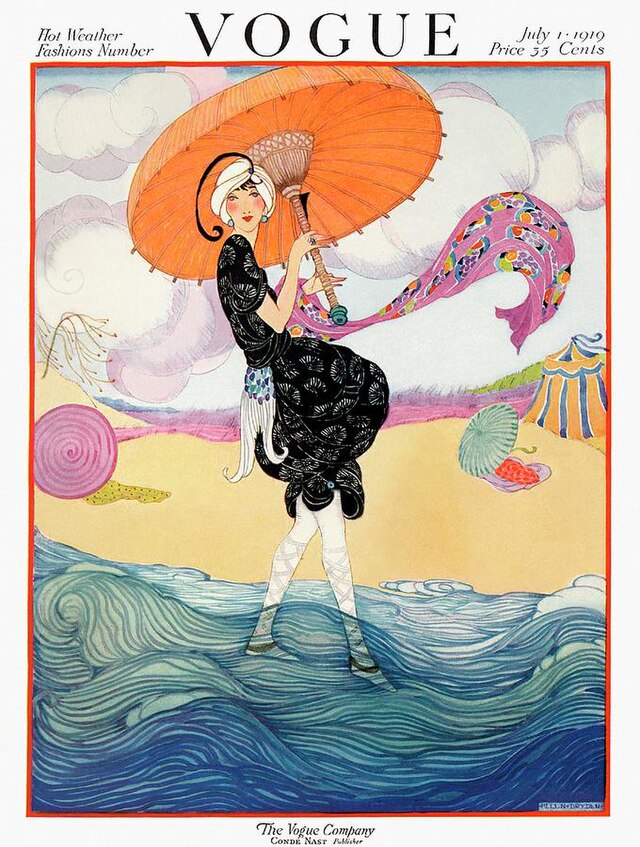

In the beginnings of Dryden’s career, illustrating for Vogue, her work was an exemplar of the trending Art Nouveau movement, consisting of thin sinuous lines, ornate detailing, and nature motifs. The term “Art Nouveau” came about when artist, Siegfried Bing, part of the Les Vingt group, named his Parisian gallery L’Art Nouveau. Dryden was educated about these happenings and had visited Paris a few times, including a trip to the 1925 Paris International Exposition of Modern Industrial and Decorative Arts. Her July 1st, 1919 cover, Hot Weather Fashions Number, reflects her travels and knowledge.

Helen Dryden, Hot Weather Fashions Number, July 1st, 1919, Wikimedia Commons

The woman can be classified as a flapper by her heavily applied makeup and bob haircut. Her outfit, a two-piece set with billowing shorts and a matching turban features a loose silhouette, resembling the whimsical qualities of the Ballet Russes costumes. Ballet Russes was a Russian Ballet company based in Paris known for their fanciful costumes designed by Léon Bakst. The flapper is seen in a prideful yet relaxed pose, like Erté’s figures that exude a sense of effortless confidence. The beach environment is imaginative due to the figure placed amongst plush purple and pink clouds and a sea made up of curvilinear lines. Dryden often created imaginative and abstract settings to enhance the artistry of the cover. The flapper woman holds a paper parasol with a wooden handle. This style of umbrella originates in Japan and became increasingly popular during the 1920s in the U.S. and Europe. Some parasols even featured hand painted designs, but here Dryden has chosen to paint the parasol a vibrant orange color. While fashion illustration was greatly influenced by Japanese artistic practices, so were the fashions and accessories themselves. While the drawing falls in line with Art Nouveau style, the color palette of rich blue, purple, and orange resembles Art Deco design.

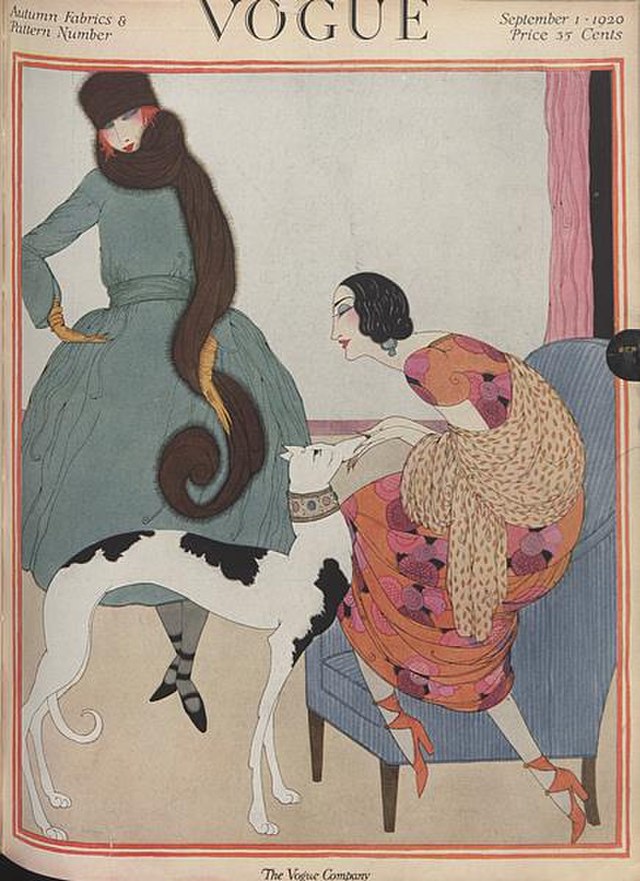

Another cover, Autumn Fabrics and Pattern Number, published on September 1st of 1920, reflects Dryden’s gradual shift from Art Nouveau illustration to Art Deco illustration. One flapper woman wears a floral dress with many folds and drapery throughout. The other has a winding scarf around her neck.

Helen Dryden, Autumn Fabrics and Pattern Number, September 1st, 1920, Wikimedia Commons

However, there are a few Art Deco motifs depicted. The Art Deco movement valued the efficiencies of the new American industrial inventions, and they conveyed this by streamlining design, often using geometric shapes to do so. The rather plain background simplifies the design while the symbolic greyhound dog, illustrated geometrically, expresses the new industrial scene. The dog’s impressive speed and sleekness served as a reference to Greyhound Lines Inc., American bus operator, established in 1914. The dog positioned next to the flapper conveys the idea that she embodies everything new and improved.

In 1923, Dryden left Vogue, and began to illustrate covers for another fashion magazine, The Delineator, a magazine of minimalist Deco design. Moving away from her curvilinear and abundant Nouveau designs, Dryden leaned into streamlined illustrations but did not stop depicting the flapper regardless of the stylistic changes.

Exemplar of Art Deco Illustration Depicts Flapper Woman for Perfume Advertisement by Beatrice Anderson

Beatrice Anderson (1910-?) was an illustrator, originally from Quincy, Massachusetts, but moved to Seattle, Washington during her teenage years. Not much is known about Anderson, however her collection of Deco designs made in 1925 is a standout amongst her works. This group of artworks was made when she was fifteen years old, indicating she might have been in art school. There is no evidence that these designs were published in the advertisements and magazines they were made for, perhaps the designs were developed as an independent project or assignment. Anderson is an example of a young woman who was pursuing illustration as a career during the "golden age" of fashion illustration in the 1920s.

One of her works, an advertisement meant for Parfums Luyna, a Parisian perfume company, exemplifies how Art Deco design was utilized to portray the flapper.

Beatrice Anderson, Design for an Advertisement for Parfums Luyna, 1925, Louisa du Pont Copeland Memorial Fund, 2007, Delaware Art Museum Collection

The strong linear elements of the silhouettes of perfume bottles and grand black chair draw the viewer’s eyes to the fair woman in an ornate outfit. The detailing of the hat and dress are expressed with geometric patterns. The dress is inspired by Parisian designer, Paul Poiret, due to the lack of a corset. The outfit is likely styled after the “lampshade design”. The lace v-neckline and lace sleeves emphasize her sexuality, and saturated blue and purples also fall in line with the Deco color palette. The decision to envision the flapper archetype as the face of the Parfums Luyna brand may have enticed women to embrace new liberating fashions and exercise their freedoms unapologetically.

Writer, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Tells Stories of the Flapper Woman Through The Saturday Evening Post Series Flappers and Philosophers

The flapper persona was cultivated through distinct imagery featured in advertisements and illustrations. The public was either intrigued or repulsed by the flapper, but consumers wanted to know more. The life of a flapper was excellently described by revered American writer, F. Scott Fitzgerald, enhancing the effect of illustration for viewers. Most well-known for The Great Gatsby, published in 1925, this fictional story was a reflection of 1920s romance and youth culture. Fitzgerald had been writing about the flapper before the release of the novel—in the early 1920s, a short stories series published in The Saturday Evening Post titled Flappers and Philosophers became a hit.

The short story Head and Shoulders was the inspiration for the series title, Flappers and Philosophers. The plot follows a genius philosophy student at Princeton, Horace Tarbox, who falls in love with flapper and Yale dance performer, Marcia Meadow. Tall and slender, Horace speaks as if he is “utterly detached from the mere words he let drop” (Fitzgerald, 1920) and makes his professors feel as though they are “talking to his representative”. Horace’s cousin, Charlie Moon, is concerned about his cousin’s sense of solitude and drab social life, so he sends his friend, Marcia, to visit Horace in his home study by offering her “five thousand Pall Malls”. Marcia “raps” at the door, and as she enters, her aura and voice “like a byplay on a harp” invades his space by sitting on his chair by the fireplace, which he has personified and named “Hume”. A flirtatious banter arises, and Marcia offers to kiss Horace, which he refuses because he believes it will become a “habit” that he cannot get rid of. Marcia claims “At’s all life is. Just going round and kissing people.” While sarcastic, there was some truth in the statement for the social butterfly. Horace attends many of her shows and dinner dates follow each performance. They fall in love and get married quickly. Together they move to Harlem where Horace quits his philosophy studies to become a clerk at a South American export company while Marcia continues to perform. Marcia refers to the couple as “Head and Shoulders” because Horace has the intellect to begin a lucrative career and she has the shoulders that shake on stage to financially support the couple. When Marcia gets pregnant and can no longer dance, Horace needs to find a way to bring in more money to support his wife and future child. He typically went to the gym each day to practice gymnastics, and fellow gym-goers encouraged him to start performing at the local theater. Horace quickly gains fame for his impressive gymnastic performances, earning a generous salary to support his family. Marcia finds herself without purpose as she stays at home while pregnant. She begins to read Horace’s philosophy books and publishes writing of her own that gains traction in various publications. Horace’s philosophical idol, fictional philosopher, Anton Laurier, visits their home to praise Marcia for her novel. Laurier claims he had read about Horace in an article titled, “It is said that the young couple have dubbed themselves Head and Shoulders, referring doubtless to the fact that Mrs. Tarbox supplies the literary and mental qualities, while the supple and agile shoulder of her husband contribute their share to the family fortunes.” The role reversal instilled immediate fury in Horace, and the novel ends with Horace strongly advising Anton Laurier to never respond to a “rap” and to have a “padded door”.

The message this story conveys, and many alike, is that a flapper woman can entice a man to abandon his potential to be swept up in love, only to turn into a person he does not recognize. As women became autonomous figures, men had to navigate new roles in relationships. Fitzgerald found inspiration for this story within his own marriage to Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald, whom he felt distracted him from his career as an author.

Cartoonist, Faith Burrows, Continues the Narrative of the Flapper through Humorous Comic Series Flapper Filosofy

Faith Burrows (1904-1997) was a cartoonist from Dayton, Ohio. She is most known for her cartoon series Ritzy Rosey, Flapper Filosofy, and Beautyettes written in the 1920s and 30s, depicting flapper fashion and lifestyle. Burrows found inspiration within her own life, as she was an attractive young woman and self-proclaimed flapper participating in the youth culture of the roaring 20s.

Flapper Filosofy, the longest running series from 1929 to 1936, typically consisted of one panel illustrating a flapper with a humorous caption highlighting aspects of flapper etiquette and social behaviors. The title promises to bring the reader into the mind of the flapper and expose her philosophy on life. The title of one panel, “Getting into the pick of condition can make one black and blue.” is a black and white drawing depicting a flapper on a sports field, wearing knit sportswear inspired by Chanel and Schiaparelli, while sitting in the middle of the frame suffering from an injury.

Faith Burrows, Getting into the pick of condition can make one black and blue., Cartoon for King Features Syndicate published in Elizabethton Star, June 8, 1931, Delaware Art Museum Acquistion Fund, 2019

The stars drawn around her head and her flustered expression indicates she was hit in the head by the ball. The reader can imagine her dazed state of mind by her large eyes and eyelashes as well as her unkempt hair. This a trivial occurrence, but also the result of women participating in sports as never before. Burrows' depictions of women playing sports was an intentional and progressive decision because these were activities historically only meant for men. Women who played sports had leisure time, made possible by their careers and new efficient industrial inventions. The flapper woman symbolized and celebrated the integration of women in the workplace and modern industrial systems.

Another panel, “About the only woman who says her husband is an angel is a widow.” portrays a flapper sitting in a garden watching a woman kick her husband out of the house, seemingly through the window.

Faith Burrows, About the only woman who says her husband is an angel is a widow., Cartoon for King Features Syndicate published in Cincinnati Enquirer, May 14, 1930, Delaware Art Museum Acquisition Fund, 2019

The flapper is chuckling while the other woman looks content with her doings, and the husband is stunned. Sporting her bob haircut and short dress, the flapper mocks the hardships of married life, relishing her freedom. The flapper fashion revolution instilled a sense of assertiveness in women that allowed them to speak their minds, with humor, of course. Here, Burrows comments on the unappealing yet relatable aspects of long-term relationships by depicting a woman who stands her ground.

A little over a hundred years later from the Jazz Age (1919-1942) the freedoms that had been granted to women during this time are now viewed as everyday occurrences in the United States. Many young women today have gone to university, pursue a career of their interests, drive their own cars, and find equal partnerships in their romantic lives. However, there was once a time when this way of living was entirely new and initially taboo. Illustration not only expressed the societal changes, but also recorded them in history, allowing women of the present to embody the freedoms that illustrators and story tellers had once advocated for.

Bibliography:

“Art Nouveau.” Britannica. June 27, 2025. Art Nouveau | History, Characteristics, Artists, & Facts | Britannica

“Beatrice Anderson.” Delaware Art Museum. Accessed: June 11 2025.https://emuseum.delart.org/people/5117/beatrice-anderson?ctx=55d1b0fb32c05dfbef6dd47ef889063923d4b006&idx=4

“Biography of Beatrice M. Anderson (1910-?).”ArtPrice. Accessed: June 11 2025. The biography of Beatrice M. ANDERSON: information and auctions for the artworks by the artist Beatrice M. ANDERSON - Artprice.com

Broman, Elizabeth. “Helen Who?? Her Life as a Fashion Illustrator, Costume Designer, and...(Part one).” Cooper Hewitt. March 19, 2016. Helen Who?? Her Life as a Fashion Illustrator, Costume Designer, and… (Part One) | Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

Broman, Elizabeth. “Helen Who?? Her Life as an Industrial Designer (Part Two).” Cooper Hewitt. March 25, 2016. Helen Who?? Her Life as an Industrial Designer (Part Two) | Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

Campbell Coyle, Heather. Jazz Age Illustration. Delaware Art Museum, Yale University Press, 2024

“Coco Chanel.” Encyclopedia Britannica. June 17, 2025. Coco Chanel | Biography, Fashion, Designs, Perfume, & Facts | Britannica

“Design for an Advertisement for Parfums Luyna.” Delaware Art Museum. Accessed: June 11 2025. https://emuseum.delart.org/objects/11877/design-for-an-advertisement-for-parfums-luyna

DiEleuterio, Rachael & Campbell Coyle, Heather. “Illustrating Flappers in the Jazz Age.” Delaware Art Museum, October 1, 2024. Illustrating Flappers in the Jazz Age - Delaware Art Museum

“Faith Burrows.” Delaware Art Museum. Accessed: June 18 2025. Works – Faith Burrows – Artists – Delaware Art Museum

“Flappers.” HISTORY. May 28, 2025. Flappers - 1920s, Definition & Dress | HISTORY

“Flapper Philosophy: Modern Women in the Jazz Age.” Delaware Art Museum. Accessed: June 18 2025. Sources and Further Reading · Flapper Philosophy: Modern Women in the Jazz Age · Delaware Art Museum, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives Digital Exhibitions

Goethe-Jones, Sarah. “Fashion Illustration from the 16th Century to Now.” Illustration History. March 12, 2019, Accessed: August 26, 2025. https://www.illustrationhistory.org/essays/fashion-illustration-from-the-16th-century-to-now.

““Head and Shoulders” by F. Scott Fitzgerald.” Saturday Evening Post. April 24, 2018. Accessed: August 26, 2025. https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/2018/04/head-shoulders-f-scott-fitzgerald/.

“Helen Dryden: Illustrator and Industrial Designer in the Age of Art Deco.” WashU Libraries. May 17, 2017. Helen Dryden: Illustrator and Industrial Designer in the Age of Art Deco - WashU Libraries

Heys, Ed. “Helen Dryden: fashion illustration and automobile hardware design.” Hemmings. August 27, 2024. Helen Dryden: fashion illustration and automobile hardware design | The Online Automotive Marketplace | Hemmings, The World's Largest Collector Car Marketplace

Jay, Alex. “Faith Burrows.” Comic Strip History. April 18, 2017. Ink-Slinger Profiles by Alex Jay: Faith Burrows - Stripper’s Guide to Newspaper Comics History

McKenna, Amy. “flapper.” Encyclopedia Britannica. December 20, 2024. Roaring Twenties | Name Origin, Music, History, & Facts | Britannica

Sessions, Debbie L. “1920s Parasols, Beach Umbrella Fashion History.” Vintage Dancer. March 10, 2021. 1920s Parasols, Beach Umbrella Fashion History

Spivack, Emily. “The History of the Flapper, Part 5: Who Was Behind the Fashions?” Smithsonian Magazine. April 5, 2013. The History of the Flapper, Part 5: Who Was Behind the Fashions?

“Tokugawa period.” Britannica. Tokugawa period | Definition & Facts | Britannica

Weyant, Curtis A. “Flappers and Philosophers by F. Scott Fitzgerald.” The Project Gutenberg. December 27, 2020. Accessed: August 8, 2025. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/4368/pg4368-images.html.