In modern times, a common way of practicing drawing is to use straight lines. The process usually consists of using straight lines to delineate the shape of the drawn object, then crossing it over or overlaying straight lines in the same direction. This affects density by using overlay sections to create a different range of values in the drawing. The use of values creates shadows that further enhance the perspective of the drawing (fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Norman Rockwell, Al (Dorne) by Norman, n.d.

When looking at work of the artist Peter Paul Rubens (Belgian, 1577-1640) in person, there is always a question of how he drew in such a way that represents the shapes and forms by using only lines. His particular drawing method is called contour lines drawing style. This style of contour line drawing coexists with straight lines, but is less favored in the current era because of its long learning curve and intensive training requirement. This article will be dedicated to learning Peter Paul Rubens’ drawing method.

To fully understand Rubens’s drawing method, recognizing how he developed his drawing style in his early life is key. His thinking and learning process are equally essential for analyzing Rubens’s drawing piece by piece.

Fig. 2. Peter Paul Rubens, Portrait of the Artist, 1623.

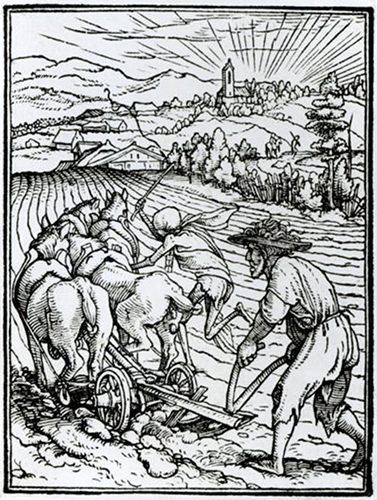

Peter Paul Rubens (fig. 2) was born in 1577 and passed away in 1640. His life started at the end of the Northern Renaissance era and in the middle of the Catholic Church Reformation. He was born in a moderately wealthy family, which later granted him access to a wide range of opportunities when deciding his career.[1] After Rubens’s father (Jan Rubens) died, the artist moved back to Antwerp, where he served as an apprentice to Tobias Verhaecht (1561–1631).[2] The earliest existing Rubens’ work is a copy after Hans Holbein the Younger’s (1497-1543) published print “The Ploughman and Death” (fig. 3).[3]

Fig. 3. Peter Paul Rubens, The Ploughman and Death, n.d. This woodcut is the earliest existing Rubens’ work,xa copy after Hans Holbein the Younger’s (1497-1543) published print “The Ploughman and Death” (fig. 3).[3]

One can see that the Northern Renaissance wood-print style was already influencing the young Rubens. His drawing copy also shows the artist’s careful methods of learning the drawing by placing inks following the original wood print. Since Rubens was copying Hans Holbein the Younger’s work, which was influenced by the Northern Renaissance, it is not hard to imagine that he might also be affected the wood print work of German 16th century artists, such as Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), Matthias Grünewald (1470-1528), and Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553).[4] Wood prints were relatively easy to obtain. There is an interesting example of this easy distribution: in the 16th century, even the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian the First (1459-1519), was spreading his well-printed portraits by Albercht Dürer and Hans Weiditz the Younger (1495-1537) for his massive promotion purpose.[5] These prints were printed in large quantities and popular across Europe.[6]

The region of Italy has often been considered the center of the Renaissance. Artists traveled to Italy to study art. For example, Dürer in his lifetime studied in Italy twice to improve his artwork, first from 1494 to 1495, then from 1505 to 1507.[7] Hans Holbein the Younger traveled to Italy in 1517 and returned in 1519, to develop his artistic style. After Peter Paul Rubens finished his apprenticeship in 1598, he also went to Italy where he stayed for eight years (1600-1608).[8] During this time, he studied classical statues and paintings. He also did drawings based on Michelangelo’s painting for the Sistine Chapel. In his unpublished Latin treatise, Rubens described his intentions on drawing statues. He avoided recognizing them as stone statues with stone texture, but rather saw them as living figures.[9] In his sketches, he learned the Italian sketch style by combining brown wash with brown inks. This style of drawing was also used by Peter Paul Rubens’ teacher Otto Van Veen (1556-1629) when Rubens served as Van Veen’s workshop apprentice from 1594 to 1598.[10]

After Rubens began his workshop in Antwerp in 1609 and had become a well-respected master, he focused his career on painting. Rubens used his drawing practices as painting ideas, and guided his student and his appointee. (Peter Paul Rubens hardly ever showed his drawings to the public, even to his students. The suspected reason for this is that his drawings at the time were more related to sketches for his paintings. An artist like him would not want to show his original ideas, being afraid that they would be copied by other artists).[11] Peter Paul Rubens was making prints in addition to having a career as a painter. Like most of the masters during the Renaissance, he did not make prints himself, but collaborated with other printmakers’ workshops or used the help of his students. He also collaborated for thirty years with his friend and printmaker Balthasar Moretus (1574-1641) from Plantin Press. Rubens was known to have full control of his artwork.[12] He strictly made his engraving artist or his assistant follow his lines and transfer his painting to drawing, without giving any engraver’s personal artistic style. After the copy was made, he would simply correct the error or the section of the drawing which he did not favor. For this reason, interpreting Rubens’ published engravings can help us reflect on his drawing thinking progress.

In the last years of his life, Rubens started to be interested in wood-cut prints again. In collaboration with Christoffel Jegher (1596–1652) around 1628, he created a large number of prints, such as Hercules Fighting the Fury, Rest on the Flight into Egypt, and The Garden of Love.[13] These prints feature 17th century clothing fashions and Rubens’s style of drawing faces, but the technique followed the spirit of the 16th century Northern Renaissance style. It almost seems as if Peter Paul Rubens was traveling back in time, and what he was working on brings the viewers into Rubens’s teenage life memories.

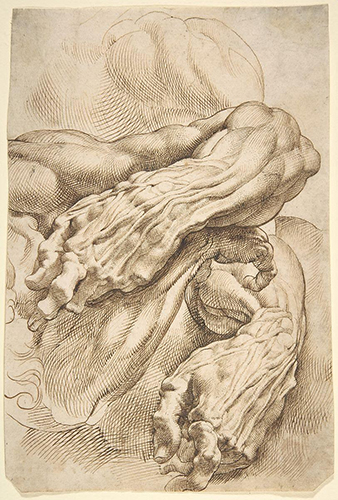

To understand the drawing technique used by Rubens one can look at his drawing Anatomical Studies: a left forearm in two positions and a right forearm (fig. 4) which is chosen here because of its clearly visible marks. It is a study drawing Rubens made ca.1600-1605 during his stay in Italy. This work is now in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Fig. 4. Peter Paul Rubens, Anatomical Studies: a left forearm in two positions and a right forearm, ca.1600-1605.

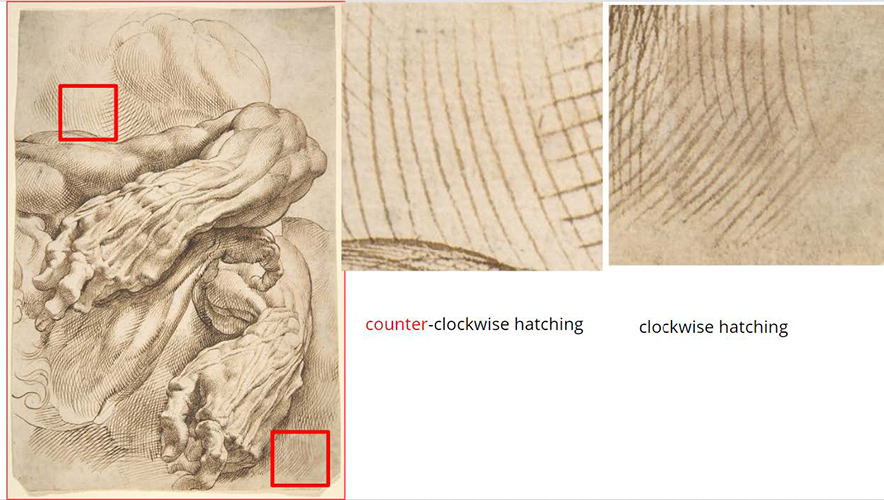

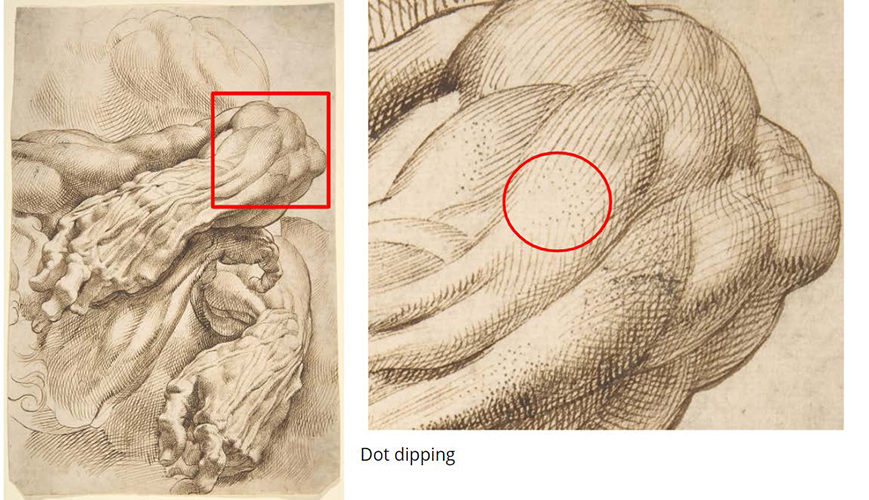

At the start of this analysis, this artwork’s mark-making can be simplified into three different drawing methods based on the right-hand movement when drawing lines: “dot pointing, clockwise line drawing, and counter-clockwise line drawing.”(fig. 5a) The dot pointing method can be spotted in the upper-center frame, on the edges of highlight close to the halftone created by the left arm’s extensor Carpi radialis muscle (fig. 5b). The clockwise line drawing and counter-clockwise line drawing methods are the dominating ways of drawing Rubens used in this artwork. The clear examples are in the top section of the artwork.

Fig. 5a. Peter Paul Rubens, Anatomical Studies: a left forearm in two positions and a right forearm [detail], ca.1600-1605.

Fig. 5b. Peter Paul Rubens, Anatomical Studies: a left forearm in two positions and a right forearm [detail], ca.1600-1605.

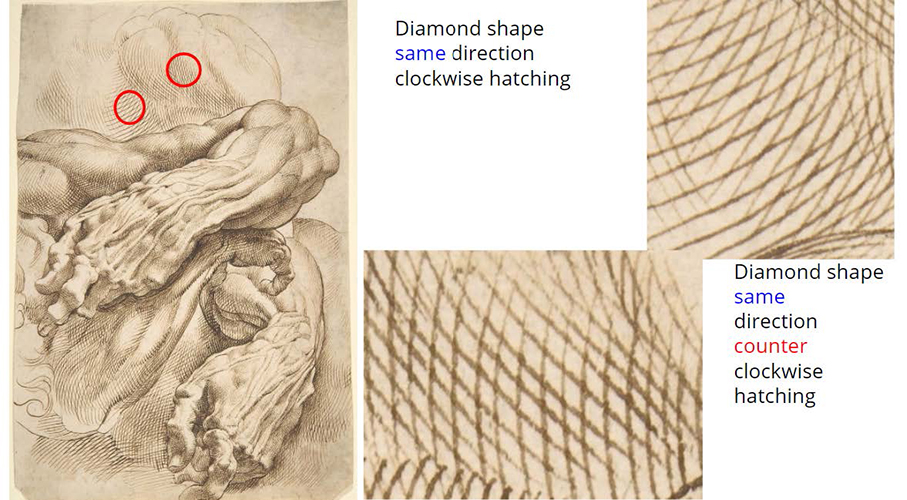

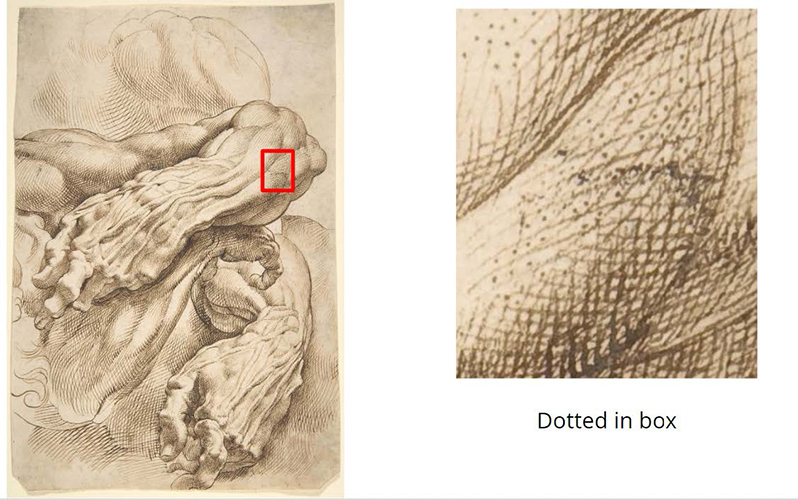

Combining these three methods generated three new drawing styles: diamond shape same direction clockwise hatching, diamond shape same direction counterclockwise hatching, and dot in boxes. These examples can be found in the majority of sections of this artwork. For a clear example, in the lower-left edge corner, Rubens used the same direction clockwise hatching on the upper left corner. In the background above the left arm muscle, he uses the same direction counterclockwise hatching (fig. 6a). At last, it also appears Rubens had used another technique. He pointed one to two dots into each box created by cross-hatching. This method can be spotted in the upper right section, on the end section of the left arm’s extensor carpi ulnaris muscle. Most of these dots are accurately dotted into the center of each hatching boxes. The diamond shape described here is based on the angle of contour lines inserted into each other; there are also different angles used in this artwork, like a larger angle’s cubic shape crossing over, but in this drawing, the usage of diamond shape-lower angles is more profound. It is impossible to have dots in the center of each box, which means these dots are dotted after the hatching lines were applied. Hence, It was Rubens’s intention to create a mid-ground value effect to transfer from halftone to shadow edge smoothly (fig. 6b).

Fig. 6a. Peter Paul Rubens, Anatomical Studies: a left forearm in two positions and a right forearm [detail], ca.1600-1605.

Fig. 6b. Peter Paul Rubens, Anatomical Studies: a left forearm in two positions and a right forearm [detail], ca.1600-1605.

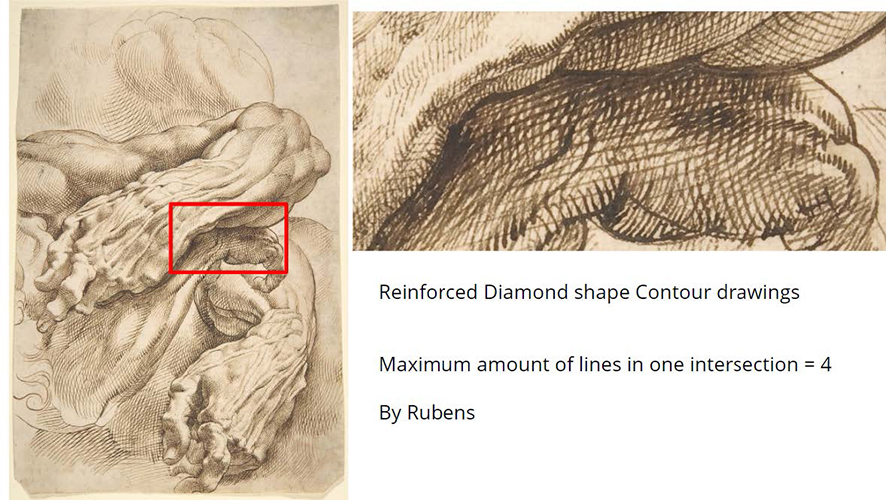

To create different ranges of values, reinforced cross-hatching is used. It is made by adding additional lines over the diamond shape hatching contour lines (the maximum number of co-existing lines in one intersection is four). To apply these lines into heavy values, once Rubens finished his outlines, he would then apply cross hatching onto the basic diamond shape hatching. These lines are often thicker than those he uses in his base layer of diamond shape hatching. The best example of this method can be seen in the center-right section of the discussed artwork, the core shadow, and the cast shadow under the left wrist (fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Peter Paul Rubens, Anatomical Studies: a left forearm in two positions and a right forearm [detail], ca.1600-1605.

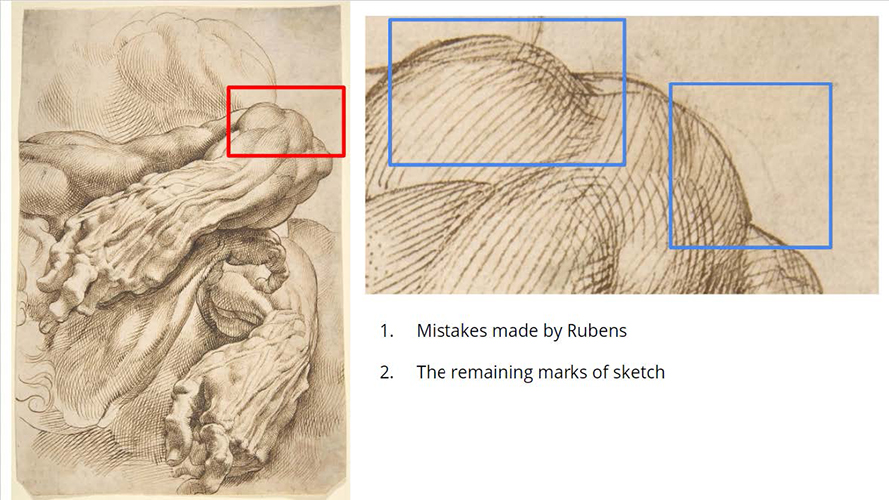

The process of Rubens’s drawing, like most of today’s drawings, started with underdrawings. Although it is hard to perceive them in this artwork, two light gray-colored marked lines followed the Flexor muscles’ end shape (above elbow). It is unclear what exactly Rubens used to create these gray lines, possibly it was silverpoint or graphite. The artist then uses a thin brown line to trace over his under-sketch drawing (with a line or two), this can also be seen in the upper left frame when he is drawing extensor carpi radialis longus and brachioradialis. He had small difficulty in outlining these two muscles. These three consistent lines have the same equal line weight, but did not share the same heavy outlines as the correction lines do. Yet, these three lines are significantly heavier than the other parallel shading lines. (Rubens must have realized that he had made a mistake, but since it is brown ink, he could not erase it from the paper. Instead, to cover up his mistake, he used lines that went in the same direction together with the shading lines) (fig. 8). After the thin outline was applied, Rubens would coat it with a stroke or with two weighted lines in order to distinguish the object from the shadow’s heavy shading and solid outline shape. In the center of this artwork, a large negative space was created under the left-hand’s paw. If Rubens wanted to showcase his proud line drawing, he needed to limit the number of lines in a single area. Without a heavy outline to divide two shadow areas, leaving space for occlusion shadows to portray shape and form are simply not enough. Rubens uses his cleverness to create a heavy outline to illustrate the core shadow and describe the left-hand paw’s form and shape.

Fig. 8. Peter Paul Rubens, Anatomical Studies: a left forearm in two positions and a right forearm [detail], ca.1600-1605.

Finally, Rubens used the drawing method mentioned above to create hand and arm’s form and shape. The wood-cut print Garden of Love is a piece made by Rubens and his workshop together with Christoffel Jegher. Three copies of this work exist; one was painted with brown ink drawing and is stored in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (fig. 9). Another one was a print version made by Rubens in collaboration with Christoffel Jegher (fig. 10) and based on the brown ink drawing, also in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection. The last one is an oil painting version, stored in the Prado Museum, Madrid.

Fig. 9. Peter Paul Rubens, The Garden of Love, 1633–1635.

This artwork (fig. 9) is a celebration of Peter Paul Rubens’ second marriage with the sixteen-year-old Helena Fourment (1614-1673).[14] The background scene features Rubens’s house in Antwerp. In the foreground, two couples are standing together. The male standing person is holding his young wife as a precious gem. With the same goat beard and tip lifting but loose imperial mustache, curly hair but partially bold, this might very well be Peter Paul Rubens himself as his self-portrait depicts (fig. 2). The garden in the background could be understood as a symbol of fertility. Placing Rubens and his wife in the foreground and the section of the building in the background mimics a traditional medieval and Renaissance structure, suggesting these background buildings and gardens are the property of Rubens and his wife. There is also a cupid-shaped angel “Cherub” on Rubens's wife’s left, putting his left hand on Rubens’s right leg and right hand on Helena’s leg. This gesture could be seen as a blessing for Rubens and Helena Fourment’s matrimony. The picture depicted Rubens carrying a rapier sword on his left waist. Wearing a sword suggests his nobility of knighthood titled by both Philip IV of Spain and Charles I of England.[15]

Fig. 10. Peter Paul Rubens, The Garden of Love, 1630s.

For our learning purposes, the drawing version of the Garden of Love (fig. 9) is a great indicator of Rubens’s drawing steps. Furthermore, the Garden of Love (wood-cut print, fig. 10), shares the exact same line technique as the ink drawing, and, in addition, it features clearly rendered details on lines. Having a combined study of these two artworks will help to further understand Rubens’s drawing techniques. Before applying ink drawing, Rubens constructed a light sketch using silverpoint or thin graphite. Even though this sketch is mostly covered by brown ink, its remains still exist in the upper left corner, around the tree branches. By studying Rubens’s previous artworks, Battle of Nude Men, Part of the Crowd at the Ecce Homo, and Venus Lamenting Adonis, one can see that the artist had a habit of working from figures to the background. The stage of the Garden of Love can be divided into three sections by grouping figures together. The obvious first group with three figures (Rubens, Helena, and Cherub) are staged in the foreground. Then the second group of a young man with a sword and a young woman looking towards the viewer is seen in the middle ground. The third group of six figures is visible in the background.

Foreground Groups of Figures

When looking at the figure drawing of Rubens and Helena Fourment, one immediately notices the different methods of contour lines ranging from clockwise, counterclockwise, diamond-shaped same direction clockwise, and diamond-shaped counterclockwise contour lines. Almost every contour line Rubens used is in the direction and form of an object. For example, Fourment’s face is simplified into three ellipses, with each line describing its form by creating negative space. Rubens then applied hair elements in an “S” shape direction curve together with invested contour lines to create negative space. By applying lines that follow shapes and forms, the artist creates a sense of three-dimensionality and a realistic portrayal of a figure or object without sacrificing the beauty of every single line.

The figure of the Cherub provides a splendid example of Rubens’s technique. The artist here used heavily weighted lines in specific areas, such as the right arm’s lower section, the front of the Cherub’s belly and chest, or right hip and leg. These parts of the Cherub’s body are closer to the viewer. Hence, the heavily weighted outline creates space and dimensions to demonstrate the figure’s position in the frame. By using previously-mentioned clockwise and counterclockwise contour lines, Rubens then created the Cherub’s chubby flesh, just like artists before him, such as Michelangelo, Dürer, or Hans Holbein, did in their drawings.

Midground Groups of Figures

Midground figures are supposed to be less important to the viewer than the foreground figures, and this is well seen in Rubens’s drawing language. Rubens uses hierarchy to draw the viewer's focus to Rubens and Helena, then to the two figures in the midground.

The young male figure in the midground is half lying on the ground with the sword on his leg, however, the proper manner of carrying a sword is on the left waist of the wearer. Disarming one’s sword completely off the belt is a sign of admitting a lower profile and showing humbleness. Rubens’ drawing of this young male figure was unlike what he did in the first group of figures. Compared with what he did to the young woman's head, with rich variation of contour lines, he used more clockwise contour lines in negative space, all in the same direction and not always following the figure’s form. The use of a counterclockwise contour line in negative space gives the viewer a sense of flatness.

On the right side of this young gentleman, is a well-dressed young lady. Although most drawing techniques that apply to this figure were already discussed above, the lady’s dress provides a great study on how the lines that go in one direction can depict an object's form, but change its spacing and curvature. (Forms featuring Cupid and/or female figures with chubby flesh had existed long before Rubens made this artwork; for instance, there are Roman statues of Centaur & Cupid dating to 1-2 CE. Having a puffed face or chubby body style was considered a sign of wealth and well-living). At the bottom of the dress, Rubens uses a combination of long single lines or a collection of short lines to emphasize the dress’s flatness and folds. The artist also used the spacing of each line, by condensing the line spacing to create negative space or enlarge the line spacing to create a color-positive space.

Background Groups of Figures

Background figures exist mainly for environmental purposes. In the Garden of Love, they are meant to promote enjoyment for the viewer. Since these figures are not as important as those mentioned above, they do not share large amounts of detail because overly describing them with lines would cause confusion with midground and foreground figures. Nearly all six of these background figures are drawn by using the same techniques. However, the woman on the very left is an interesting example. Rubens’s rule of using lines that follow the form is nearly abandoned and almost every line used here is clockwise contour hatching. This helps to flatten out the figure.

Conclusion

Rubens’s drawing method may seem difficult to understand when one analyzes his drawings as a whole, but can be more easily explained when we have the chance to study these works in sections. As written by the Chinese philosopher, Lao Tzu (600 - 400 BCE), “The Dao produced One; One produced Two; Two produced Three; Three produced All things.”[16] From basic contour lines to “dot in box,” it is the mastery of basic line drawing method used by the artist that enables us to further interpret the complex forms of Rubens’s drawings.

[1] Charles Scribner, “Peter Paul Rubens,” Encyclopædia Britannica. June 24, 2020. Accessed December 18, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Peter-Paul-Rubens

[2] Ibid.

[3] Kristin Lohse Belkin, “Rubens's Latin Inscriptions on His Copies after Holbein's Dance of Death.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 52 (1989): 245-250.

[4] Victoria Charles, Renaissance Art (New York: Parkstone International, 2012), 65-79.

[5] Andrew Robison and Klaus Albrecht Schroder, Albrecht Durer Master Drawings, Watercolors, and Prints From Albertina (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2013).

[6] Larry Silver, Marketing Maximilian: The Visual Ideology of a Holy Roman Emperor (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008).

[7] Heinrich Theodor Musper, Albrecht Dürer (Cologne, Germany: DuMont-Literatur-und-Kunst-Verl, 2003), 5-7.

[8] Anne-Marie Logan, Peter Paul Rubens: The Drawings (New York: Metropolitan Museum Of Art, 2013), 5.

[9] Ibid., 6.

[10] Scribner, “Peter Paul Rubens.”

[11] Logan, Peter Paul Rubens: The Drawings, 4.

[12] “Rubens and His Printmakers” (Getty Center Exhibitions). September 24, 2006. https://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/rubens_printmakers/#

[13] Logan, Peter Paul Rubens: The Drawings, 257-267.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Scribner, “Peter Paul Rubens.”

[16] James Legge Laozi and Zhichao Gao, Dao De Jing: Tao Te Ching (Zhengzhou Shi: Zhong zhou gu ji chu ban she, 2016).

__60_60_c1.jpg)