Polish posters of the second half of the 20th century contributed significantly to modern visual culture and museums, collectors and design educators around the world recognize their significance. Known as “the Polish school” of poster design, these works, while stylistically diverse, can be recognized as part of a unified, and ultimately national, approach to poster art that reflected the soul of a population during a long period of repressive governance and political unrest.

Origins

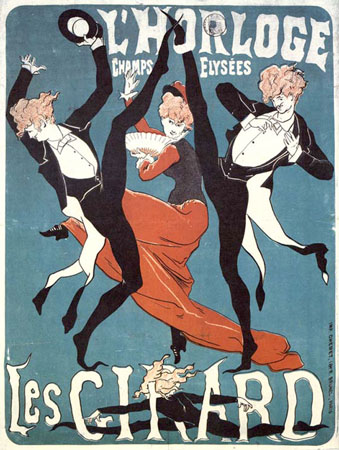

The “art poster,” which had its beginnings with the French lithographer Jules Chéret around 1880 [Fig. 1], was an artful means to a commercial end: the transmission of an advertising message. Nineteenth century poster artists, many trained as painters, applied their skills to graphic designs which advertised products such as champagne, beer and cigarette papers, or promoted bars and nightclubs, magazines, newspapers, steamship lines, railroads, sporting events or tourism. Posters were also created for promoting cultural events such as exhibitions, concerts, theatrical productions and, then in the twentieth century, film showings. Throughout history, posters have also been used to express political positions, proselytize, propagandize or convey information that has social importance. The poster is both a tool and an art form, and throughout world cultures nowhere has it been used more meaningfully than in Poland.

Fig. 1. Jules Chéret, venue poster (France), Les Girard, L’Horloge, 1879

During the entire nineteenth century and most of the twentieth, the territory now called Poland was under siege from the expansionist efforts of competing empires. Napoleon’s French Empire, the Russian, Austrian and Prussian Empires, Hitler’s Nazi Germany and then the Soviet Union all vied for control of Polish lands and suppressed ethnic Polish nationalism. Poles resisted.

“Much of the legend and symbolism of modern Polish patriotism derives from this [threat] … including the conviction that Polish independence must be a necessary element of a just and legitimate European order.”[1]

Poles struggled mightily to maintain their sovereignty as a people, and throughout the turbulent history of their nation, Polish artists, writers, composers and designers have reflected their traditions and expressed their cultural sensibilities through the arts.

Fig. 2. Karol Frycz, advertising poster for cigarette papers, Tutki, c. 1900

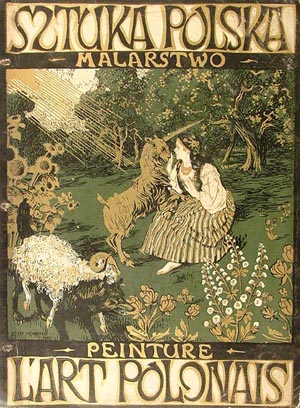

Fig. 3. Jozef Mehoffer, exhibition poster, Polish Painting, 1903

Figures 2 and 3 both reflect an ethnic Polish style based on folk art. Design motifs, patterns and letterforms typical of regional cultural heritage were seen in Polish posters like these up until the First World War. The poster by Jozef Mehoffer from 1903 [Fig. 3] reflects that heritage through the flat, simplified drawing style and the limited, muted coloring of the lithography. This effect deliberately relates to the woodcuts that were historically used to illustrate books of ethnic folk tales and fables. Mehoffer, a skilled portrait and landscape painter, intentionally produced this folk-inspired design to honor Polish heritage, while creating a poster for an exhibition of Polish paintings. It is important to note, however, that the hand lettering shows the influence of Art Nouveau letterform design. At the turn of the 20th century, Polish poster artists could not help reflecting the compelling Western European influences of French Art Nouveau, German Jugendstil and Austrian Secessionstil.

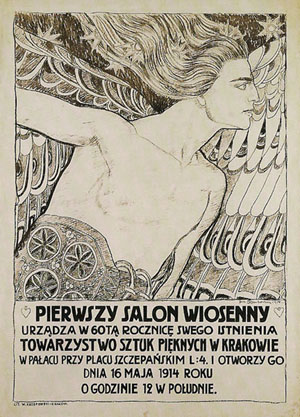

Fig. 4. Jan Rembowski, exhibition poster, Salon Wiosenny, 1914

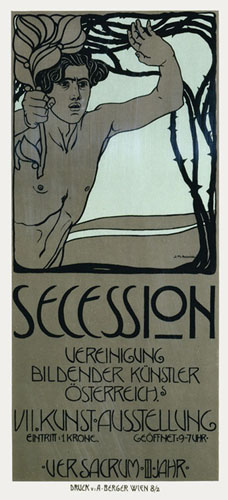

Fig. 5. Josef Maria Auchentaller, exhibition poster, Secession, 1900

Figure 4 shows a Polish poster for an exhibition in 1914 and Figure 5 is an Austrian design announcing an annual exhibition of works by members of the Vienna Secession in 1900. Comparing these it’s clear from the similarities of structure, line, pose and classical inspiration that there are aesthetic and stylistic links between them, but the Polish poster retains its ethnicity through native decorative patterns and ornament.

Fig. 6. Teodor Axentowicz, exhibition poster, Sztuka, 1898

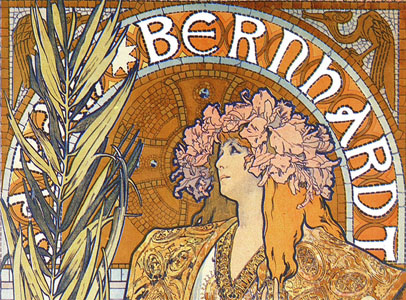

The Society of Polish Artists (Sztuka) held the First International Exposition of the Poster in 1898 in the city of Cracow. An exhibition poster by Teodor Axentowicz [Fig. 6] shows strong Art Nouveau influences in the pose and through the use of a heavy, defining contour line surrounding the form which contrasts with the delicately rendered features of the face. This graphic approach is similar to that used by Alphonse Mucha for the posters he created while in Paris in the 1890s [Fig. 7]. Mucha, from the Moravian region of Czechoslovakia, brought Slavic elements into his posters through portrayals of ethnic costume, fabric patterns and ornament, even though these works were created in France.

Fig. 7. Alphonse Mucha, theater poster, Gismonda, Theatre de la Renaissance, 1895

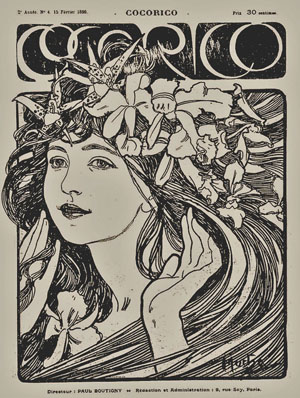

Fig. 8. Alphonse Mucha, magazine cover, Cocorico, Vol.2, No. 4, February, 1899

As Mucha often did in prints and posters, Axentowicz has used a leafy garland to surround the subject’s head in the Sztuka poster—a folk style traditionally worn at spring festivals in many Slavic countries including Poland and Czechoslovakia. The work therefore expresses Axentowicz’s heritage as well as his awareness of contemporary European design trends.

World War, Nationalism and the Beginning of Poster Design Education

At the outbreak of the First World War, Poland’s partitioning powers—Austria, Germany and Russia—in a bid for Polish loyalty, each declared their intention of making Poland a semi-independent state. The war, however, soon diluted Austrian and German strength of purpose regarding Poland, and Russia was swept up in the Bolshevik revolution. The Treaty of Versailles that ended the war in 1918 confirmed Poland’s right to independence, and for the first time in 120 years Poland was free. There continued to be disputed borders, however, and Polish nationalists attempted to take back parts of ethnically Polish territories in Ukraine and Lithuania. This led to Russian counteroffensives and the Russo-Polish War of 1920. Bolshevik troops advanced to within range of attacking Warsaw, but Polish armies succeeded in pushing them back [Fig. 9].

Fig. 9. Kamil Mackiewicz, war poster quoting a patriotic song: Poles to the Bayonet, 1920

A treaty was signed in 1921 that finally settled the disputed boundaries and formally established an independent Polish state. Poland spent the next 18 years of independence in reconstruction and rebuilding the economy. There were great advances made in industry, mining and farming that pushed forward a steady recovery in spite of the effects of the world economic depression that began in 1929 and spread throughout Europe in the 1930s.

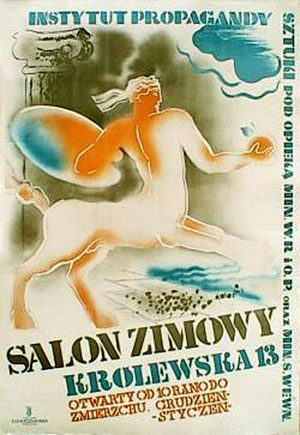

In this period between the two World Wars, artistic influences from neighboring Germany, Russia and Czechoslovakia were naturally being felt by artists in Poland, and Western European movements like Cubism and German Expressionism were attracting Polish followers. The geometric stylizations of French Art Deco were especially appealing to Poland’s students of design and architecture.

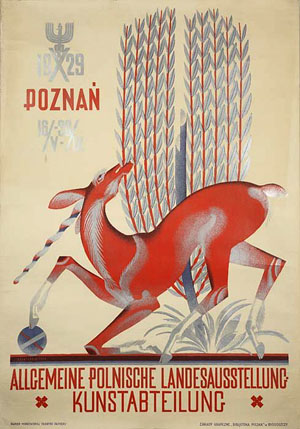

Fig.10. Edmund Bartlomiejczyk, exhibition poster, Polish National Exposition of 1929, City of Poznan. German language version, 1929

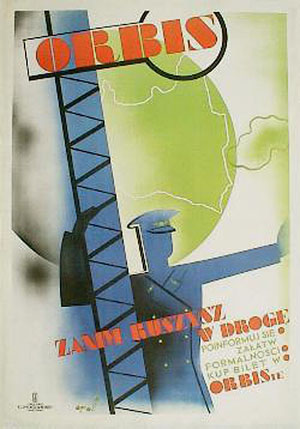

Fig. 11. Tadeusz Gronowski, advertising poster, Orbis, 1932

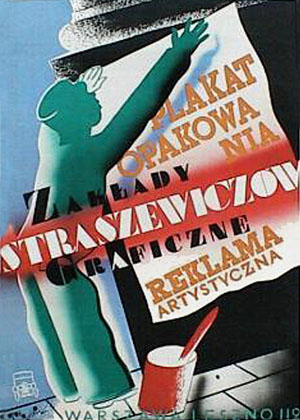

Edmund Bartlomiejczyk [Fig. 10] and Tadeus Gronowski [Fig. 11] both attended Warsaw Polytechnic Institute’s Architecture Program and became the earliest influential practitioners of modern Polish poster design.

The Warsaw Polytechnic Institute “was the training ground for many of Poland’s poster artists in the period between the two World Wars. These artists had less affiliation with and less devotion to the painterly traditions. Understanding the poster as an advertising tool, they recognized the need for rapid communication of information and found it within a geometric and architectonic poster structure.”[2]

Bartlomiejczyk taught at the Polytechnic and then became a professor at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, where Poland’s first courses in poster design began.

Social Realism

In the 1920s and 1930s, under the influence of socialist ideology, the arts of many countries came to reflect social realism. Its goal in both fine and applied arts was to honor the ordinary worker, farmer, soldier, good citizen, their families, and a strong community that was held together by a benevolent political system. Russia had been using this approach since the revolutions of 1917-1918, influencing Slavic countries, including Poland, where it meant to demonstrate the people’s strength of common purpose, as well as ethnic and national pride. Ironically, Nazi Germany used the very same approach in its own propaganda graphics, while suppressing national pride in the countries it conquered and occupied.

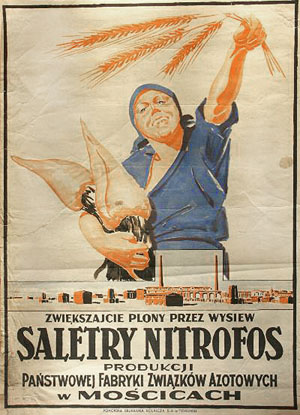

Fig. 12. Anonymous designer. Advertising poster for a fertilizer factory, 1931

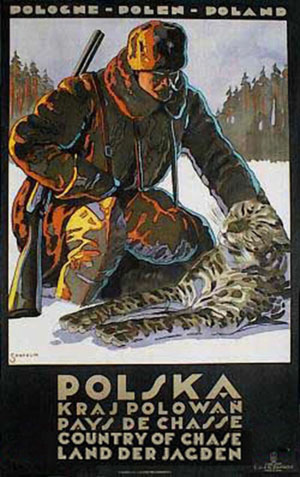

Fig. 13. Stefan Norblin, tourism poster, Poland, Country of Chase, 1927

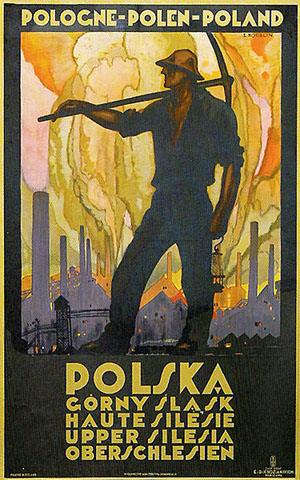

Fig. 14. Stefan Norblin, tourism poster, Upper Silesia, 1925

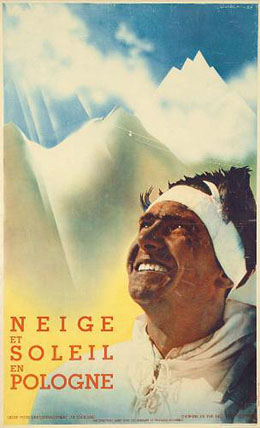

Fig. 15. Stefan Osiecki, tourism poster, Snow and Sun in Poland, 1938

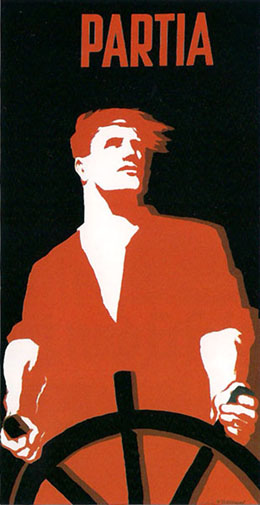

In Poland, social realism varied considerably in style during the period of the 1920s through the 1950s—from utilitarian figurative art [Fig.12] to the boldly graphic tourism posters of Stefan Norblin [Fig. 13, 14], to decorative realism [Fig. 15] and to graphic simplification as shown in a poster from 1955 by Wlodzimierz Zakrzewski [Fig. 16]. Zakrzewski was an active Communist Party member, professor at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, and founder of a state-supported poster design studio. The image in Figure 16 symbolizes steering the ship of communism proudly into the future.

Fig. 16. Wlodzimierz Zakrzewski, poster for the Polish Communist Party, Partia, 1955

Fig. 17. Wojciech Weiss, oil painting in Socialist Realist style, Manifesto, 1950

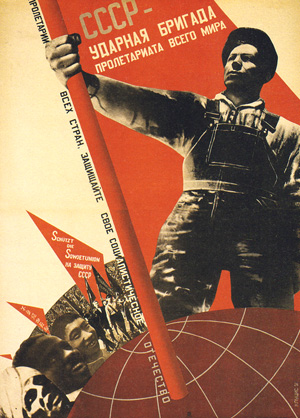

After the Second World War a more rigid socialist aesthetic and philosophy of art called Socialist Realism was imposed by Joseph Stalin throughout the Soviet Union and enforced through a bureaucratic system of censorship and approvals directed by ministries of culture within the government. The style featured literal realism and overtly political, military and patriotic content [Fig. 17], with portrayals of proud, laboring, demonstrative citizens or soldiers united in their socialist ideology, an approach which began in the 1920s and 1930s in the Soviet Union [Fig. 18]. Realism was the only sanctioned approach for fine art and artists throughout the U.S.S.R. and Eastern Bloc countries (including Poland). Artists who were inclined towards abstraction or subjective painting were stifled in their attempts to exhibit their works in galleries, but poster designers sought ways to bend the rules and subvert the restrictions placed upon them by pushing the boundaries of realism and becoming deft in the use of metaphor and allusion.

Fig. 18. Gustav Klutsis, propaganda poster (U.S.S.R.), 1931

The Bridge to Modernity

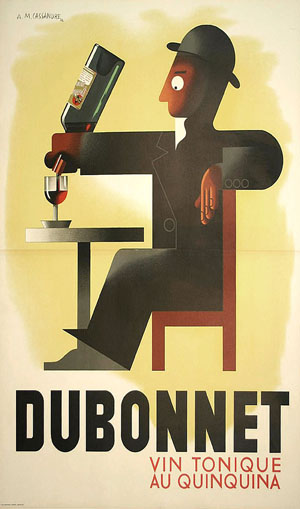

“L’Art Moderne” in France in 1925 (later called “Art Deco”) was a compelling stylization that dominated commercial and decorative arts during the late 1920s and early 1930s. It became an important international influence much as the earlier French style movement Art Nouveau had. Advertising posters by French artists Jean Carlu [Fig. 19] and A.M. Cassandre [Fig. 20] were widely posted in Paris and attracted international attention as representative works in the modern style. Both artists utilized the airbrush, a graphic arts tool that uses compressed air for spraying watercolor or inks in order to obtain even tones and gradients in illustrations or to retouch photographic prints.

Fig. 19. Jean Carlu, advertising poster (France), Pép Bonafé, 1928

Fig. 20. A.M. Cassandre, advertising poster (France), Dubonnet, 1932

Tadeusz Gronowski (1894-1990)

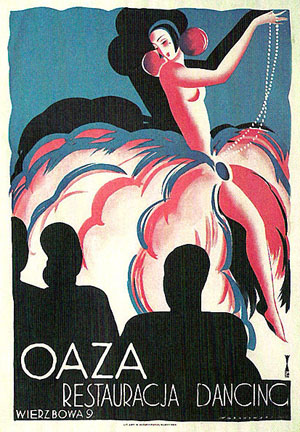

In Poland, the artist most responsible for directing poster art into modern form was Tadeusz Gronowski [Fig. 21-24]. After attending the Warsaw Polytechnic Institute as an architecture student, Gronowski studied painting in Paris at the École des Beaux-Arts and traveled frequently to that city between 1924 and 1936 in order to work as a decorative display designer for Parisian department stores. His poster work in Poland was clearly influenced by the abstracted shapes, color palettes and airbrushed gradients typical of Art Deco style and the work of Cassandre, who may have even personally introduced Gronowski to the tool and its applications.

Fig. 21. Tadeusz Gronowski, advertising poster, Oaza, 1926

Fig. 22. Tadeusz Gronowski, poster exhibition, 1932

Fig. 23. Tadeusz Gronowski, art exhibition poster, 1931

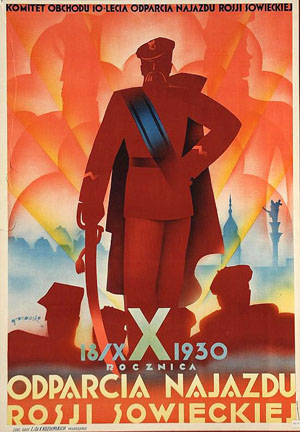

Fig. 24. Tadeusz Gronowski, commemorative poster, Tenth Anniversary, 1930

Figure 24 is Gronowski’s 1930 commemorative poster for the tenth anniversary of the victory over the Russian Bolsheviks in the invasion of Poland in 1920. It depicts the hero of that conflict, Jozef Pilsudski, who became Poland’s nationalist leader during the years of independence that followed. He stands in front of the city of Warsaw and above representations of past heroic military leaders Prince Poniatowski and Tadeusz Kosciuszko. The broken, symmetrical geometries of the red sky, the soft gradations of tone and the simplified, silhouetted shapes are typically Art Deco, but applied now to a patriotic purpose rather than a commercial one. Gronowski excelled at creating dynamic graphic designs that were fully contemporary in modern European style and technique, while at the same time his subjects showed an implied sense of community and pride of work and country. This ability may have been the primary reason that his art was both appreciated by the public and approved of by the state—thereby loosening censors’ expectations of more literal realism. Most importantly, his work provided the bridge to the mid-20th century poster design that would become legendary as the Polish school.

Invasion, Occupation and Post-War Changes

In 1939 Nazi Germany invaded Poland from the west, beginning the Second World War and ending Poland’s brief period of national autonomy. Within two weeks, the USSR, led by Josef Stalin, invaded eastern Poland to counteract Germany’s incursion and to secure territory for itself as a step towards the further expansion of Soviet domination over the neighboring Slavic world. Both invading forces fought for control of the country. Poles, their sovereignty as a nation over, responded with a resistance movement during the war, but nearly 6 million died during the fighting and forced labor and through the German exterminations of Polish Jews and nationalists. Many of the country’s intellectuals and artists were among the dead, but some survived, like the caricaturist Eryk Lipinski, who joined the Polish resistance as a document forger. Lipinski was arrested by the Nazis, imprisoned and then sent to the German concentration camp at Auschwitz, Poland, becoming one of the fortunate ones to survive internment there. After the war he resumed his work as a cartoonist and poster artist and became curator of the First International Poster Biennale in 1966.

During wartime occupation between 1939 and 1945, few Polish artists could support themselves and few posters were produced. Commerce had slowed to subsistence levels, and the few businesses and industries that remained functional were not expending money on advertising and promotion. The artistic “event poster” had always been a staple in outdoor advertising, but cultural events became virtually non-existent, since venues for concerts, opera, theater and film were closed or destroyed by bombings during the siege of Warsaw at the beginning of the German invasion.

More destruction occurred during the Warsaw Uprising in 1944 and continued throughout 1945 as the German army retreated. Most of the city was destroyed in the six-year period that Germany and Soviet Russia fought for supremacy. Poland was devastated. One fifth of its population had died as a result of the war. The country’s industrial capabilities, communication and means of commercial transportation were destroyed. Schools and universities were closed, and all the arts came to a virtual halt, including poster design, where only a small number of works were produced for propaganda purposes and to inform the public about services.

Near the end of the war, the Soviets took complete control of the country and installed Communist Party leadership that led to the creation of the Polish People’s Republic (PZPR). This “People’s Poland” was a pro-Soviet government of appointed Polish officials who were responsible to Soviet communist overseers, typical of the regimes being set up by Joseph Stalin in other “Sovietized” regions after the war, as he sought stronger control over Eastern Bloc countries.

Stalin was systematically “abandoning the prior appearance of democratic institutions.”

“In the late 1940s PZPR rule grew steadily more totalitarian and developed the full range of Stalinist features then obligatory within the Soviet European empire: ideological regimentation, the police state, strict subordination to the Soviet Union, a rigid command economy, persecution of the Roman Catholic Church, and blatant distortion of history, especially as it concerned the more sensitive aspects of Poland’s relations with the Soviet Union. Stringent censorship stifled artistic and intellectual creativity or drove its exponents into exile. At the same time, popular restiveness increased as initial postwar gains gave way to the economic malaise that would become chronic in the party-state.”[1] Ibid

Fig. 25. Poster kiosk in Warsaw with German notices, 1940

War-damaged cities slowly began rebuilding, and the wooden barrier walls surrounding construction sites became free public galleries when posters were pasted onto them. State-sanctioned or not, posters were produced, even if on small, portable lithographic presses using cheap paper and printed in limited color. The art of the poster had only been blanketed, not destroyed, and as culture began to rise from the ashes so did the poster art that served it.

Universities and art and architecture schools were reopened. Theaters were repaired and even newly constructed for the staging of plays, opera and concerts, or for showing cinema. Performances of contemporary music and jazz began to reappear, and all of these offerings required advertising. Posters were the best and customary way of doing that.

Artists found it difficult to practice in a severe post-war economy, where art materials were expensive and in short supply and where commissions and patronage came only though a bureaucracy of government agencies and state-approved industries. Private art galleries were not permitted under communism, and so artists had few opportunities for displaying and selling their work. In the USSR and Eastern Bloc countries (Soviet controlled “independent” republics), artists were advised to use only Soviet-approved approaches to painting, sculpture and poster design, and their works were reviewed by censors looking for politically subversive or other objectionable content.

Certain of the arts were being afforded favored status as outstanding examples of Soviet cultural achievement worthy of state support. Polish filmmakers and poster designers, for example, were actually encouraged, paid reasonably well and offered subsidies and direct government commissions. But posters had to be approved by a commission, marked with approval codes at the time of printing and then signed-off on personally by a censor, making the state into patron, dictator and watchdog all at once.

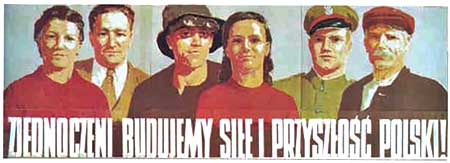

A state-sponsored poster design studio was even opened in the city of Lublin for the creation of propaganda posters, thereby establishing poster design as an approved and necessary art form. The communist artist/designer Wlodzimerz Zakrzewski [Fig. 16, 26], a landscape painter who had studied art in Moscow during the war and designed propaganda posters there, was assigned the task of establishing formal guidelines for successful graphic propaganda. This would include certain expectations in the use of language and message as well as of style, technique and imagery.

Fig. 26. Wlodzimierz Zakrzewski, propaganda poster, “United we build the strength and future of Poland,” 1952

There are a number of reasons why poster design was able to thrive in post-war Poland in spite of censorship and general repression of the society. The people’s desire for the reinstatement of cultural venues and performances was a primary one, but also:

“It was the result of a particularly felicitous combination of factors. First, the totalitarian state with unlimited funds at its disposal turned out to be a very good patron. Second, given the general shortages of everything from toilet paper to washing machines, posters weren’t really about advertising, they were art for art’s sake. Third, the primitive state of printing techniques precluded any easy, conventional use of photographs, so the artists were obliged to be more creative. Isolation from the artistic currents in the West was also an advantage—Polish artists followed their own personal creative pathways. And because in Poland there was no art market to speak of (art dealers were considered ‘rotten bourgeois’), poster-making offered one of the few opportunities for artists and designers to practice their profession.”[3]

Without the traditional gallery and art marketplace, the post-war art profession held little promise, but poster art was growing in public popularity, and its production was supported by the state. Since poster creation offered at least the possibility of a supportive income, many Polish painters (as well as those originally trained as designers and architects) began to practice art with a focus on posters. For many it would become not only their primary means of support but also their primary form of expression.

Poster art enfolded illustrative, decorative, commercial, graphic and fine arts into a public art, both accessible and attractive, which reached into the lives of ordinary citizens as they walked through the streets of their cities. It had become a very attractive field and was even on its way to being considered a legitimate means of artistic expression on a par with painting. In fact, the ability of an artist to achieve notoriety was becoming dependent upon establishing a reputation in poster design.

Art education had been another casualty of the war but programs were being reinstated and the first generation of Polish poster designers gathered students and formed poster design courses at the major universities. The most important and influential teachers of the post-war era were Tadeusz Gronowski, Jozef Mroszczak, Henryk Tomaszewski and Thadeusz Trepkowski. Poland’s half-century long era of conceptual posters began with the work of these men.

The education at the Warsaw and Cracow Academies of Art and the programs at art schools in other Polish cities such as Lublin and Lvov were formal, thorough, and produced many successful artists who followed in the footsteps of their teachers. What these artists shared, students and teachers alike, was a philosophy that placed emphasis not only on using visual tools to attract and engage a viewer, but also on the making of messages that communicate the essence of an idea or the personal interpretation of narrative content.

Even today, in Poland as well as in the Czech Republic and other European countries, programs in poster design provide a framework for teaching principles of visual communication, conceptual thinking, typography and illustration.

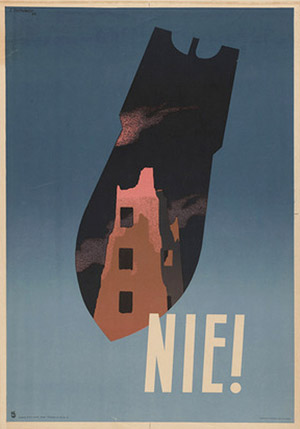

Fig. 27. Tadeusz Trepkowski, political poster, “Nie!”(“No!”), 1952

Tadeusz Trepkowski (1914-1954)

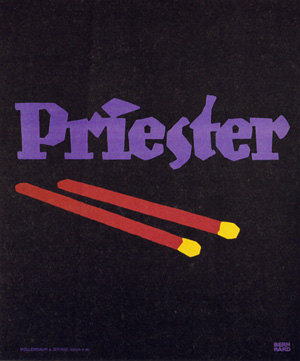

In Trepkowski’s “Nie!” poster of 1952 [Fig. 27], there is a clear message provided by universally understood symbols that have been abstracted into basic, signifying shapes. The simple directness of this composition had precedent in the work the English designers known as The Beggarstaffs who in the 1890s were the first to simplify and reduce poster design to the essence of its communication. Lucien Bernhard, a German poster artist, continued The Beggarstaffs approach when he created the reductive advertising poster for Priester matches in 1906. The German term "sachplakat" ("object poster") was coined to describe this kind of design and throughout the 20th century it would remain a powerful way of attracting attention to posters and billboards.

Fig. 28. The Beggarstaffs, theater poster (England), Hamlet, 1895

Fig. 29. Lucian Bernhard, advertising poster (Germany), Priester, 1906

What makes Trepkowski’s own understated design approach so distinctive is that his posters went an important step further. By using a combination of symbols rather than only one, he produced a message that was more complex and thereby more affecting to its audience. In just a moment, the passer-by is engaged in a process of deduction and realization, and the poster becomes a communication system for stimulating and engaging interaction. It compels a viewer to spend some time in the act of “reading” and relating to the visual/verbal message, and this has the potential to provide a deeper, more personal effect and response.

In Trepkowski’s "Nie!" poster, the bomb, as well as its effect on a city, are a conjoined visual message. When text and image are juxtaposed the message is a protest, a command, and a warning. It is an object lesson—powerful and clear—that entreats the viewer to never allow this destruction and is therefore also a rallying cry to join in preventive communal action. The message was especially affecting to its audience at the time, since the bombings of Warsaw during the war left only one in four buildings standing, and the rubble was still in evidence around the city. The threat of further war was made palpable by the poster’s design.

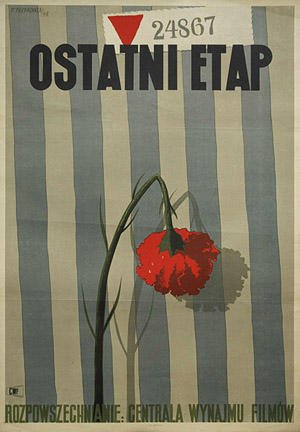

Fig. 30. Tadeusz Trepkowski, film poster, The Last Stage, 1948

Another, earlier Trepkowski poster interprets a Polish film of 1948 (one of the first films to be made after the war), The Last Stage. In that design [Fig. 30], Trepkowski shows a broken carnation—a traditional symbol of remembrance—to signify the martyrdom of concentration camp prisoners. The background stripes show the colors of the prisoner uniforms worn at Auschwitz and there is a prisoner identification number at the top.

“Such a quintessential Trepkowski poster illustrates his basic premise in poster design: it is the challenge of the artist to draw upon the viewer’s vast and hidden store of associative capacities, encouraging the viewer to participate actively in the reception of the message.”[4]

After 1950 the conceptual poster became a critically important tool in the social and political history of Poland, and, from this point on, the use of symbolism, visual metaphor or analogy to communicate idea-messages would become the most common approach to poster design throughout the world. Poster designers recognized that by engaging a viewer in an interaction that at first challenges comprehension and then provides it through the recognition of associations and semiology, their work has the potential to instill deep, personal meaning. This in turn may lead to viewer reaction and action.

Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953 brought a more liberal faction of Polish communists into power and beneficial social reforms were instituted, but poor governance badly damaged the economy over the next decade. In the 1960s unemployment, political corruption, religious repression and student unrest created a national feeling of despair. To the general public, the posters seen pasted onto walls, construction barriers and kiosks represented the sustainment and encouragement of cultural life in the midst of political, bureaucratic and regulatory oppression and economic depression. They also provided hopeful, colorful images throughout the ordinary streets of the cities.

While other trades and professions suffered in the depressed economy, poster artists and the studios that employed them were able to earn income from their design efforts. This was made possible through commissions from state-supported institutions—including cultural organizations—and from government agencies. Posters for stage productions, jazz concerts, the circus and other cultural events were being created, distributed and seen on a regular basis.

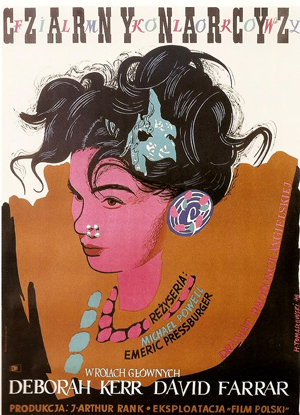

Fig. 31. Henryk Tomaszewski, film poster, Black Narcissus, 1947

Henryk Tomaszewski (1914-2005)

In 1957 the poster artist Jan Lenica said “Ten years ago Henryk Tomaszewski’s poster for the film Black Narcissus ushered in a new graphic era. The creation of such a poster was, of course, only possible in conditions offered by a nationalized film industry which did not force its requirements too dramatically upon the graphic artist but rather emphasized the importance of the educational factor in posters to mold the taste of the audience. The poster is a sort of primer from which the reading and understanding of painting may be learned, helping the onlooker to become accustomed to the forms and language of art. Greater liberty in the expression of ideas, a pleasant atmosphere of cooperation and a positive spirit of rivalry among practitioners helped to enable the Polish (film) poster to achieve such a high artistic level.”[5]

Soon after the war, Tomaszewski was producing posters for a state-run film distribution agency and in 1947, through a personal connection to an official, began to negotiate with the Ministry of Culture for the easing of restrictions on artists. The ministry was aware of the public’s appreciation for cultural events posters and the artists who were creating them, and so gradually, even though there was still censorship of content, the matter of style became much less of an issue than it had been under direct Soviet rule.

Early in their careers, Tomaszewski and Trepkowski changed the way film posters looked in Poland. Rather than showing actors engaged in actual scenes from the film, as movie posters all over the world traditionally did, they created a subjective interpretation of the film’s essence. Polish works were more similar to the kind of art that appeared on book dust jackets than to movie posters—making them more personal and also more deductive. These posters interpreted plot and character in ways that intrigued or surprised the viewer, instead of providing a literal representation of the narrative.

Imagery was used to provide connective threads that stimulated comprehension and further reflection on the subject of the film, as interpreted by the artist. Irony, sarcasm, visual metaphor, “hidden” meanings and symbolism were tools which had to be mastered so that they could be employed with facility and clarity, making the interaction between artist and viewer a communicative experience. Those same tools enabled Polish artists practicing in a repressive society to use their skills to make subtle jabs at the political establishment and create cohesion in dissent.

“It became a challenge to poster artists to satisfy the demands of the authorities while meeting the critical expectations of a defiant people. As more young artists were attracted to this impudent form of expression poster art seemed to spring from the very cracks of ruined streets.”

“Viewers judged the performances of the artists as one would the dizzy and dangerous routings of tightrope walkers. Both the people and the artists knew the limits of protest and distinguishing between public compliance and private rebellion. An artist could bite the hand that fed him, but not too hard.”[6]

The state-controlled Polish Film School came into being in 1955 for the purpose of training native filmmakers, and the state film industry sanctioned the importation and showing of foreign (European and American) films. Unrestricted by American or European movie poster advertising formulas, or by Soviet Socialist Realism, poster artists were free to freshly interpret the films in personal, graphic ways for Polish audiences.

The state Publishing Agency, Wydawnictwo Artystyczno Graficzne (WAG), supported the creation of hundreds of posters each year for cultural events, providing comfortable income for the leading poster artists. In 1966, Poland held the First International Poster Biennial, and, in 1968, the world’s first poster museum was established in Warsaw. By the 1970s, posters were so popular that the government, although still monitoring for subversive content, eased censorship and sponsored design competitions. Winners were awarded prizes and allowed to compete internationally, and poster artists were given solo exhibitions in state-run galleries. Polish poster design was becoming a source of national pride.

“The individual character of Polish posters is first and foremost due to the very personal and emotional approach of their artists. Conspicuous individualism, ever so often attributed to the Polish national character, determined the form of Polish posters at the beginning of their post-war development. Both the concepts and designs were based on the premise of the social mission of art, inherent in the consciousness of Polish society. Thus the poster ceased to be a mere means of presenting an object or service but began to interpret and comment on it. The poster began to function as a specific branch of art, ruled by its own principles and began its evaluation in the 1950s as its own means of expression, that the poster, despite its natural limitations can be as sensitive, elastic and deep a way of expressing the author’s attitude as any other branch of art.”[7]

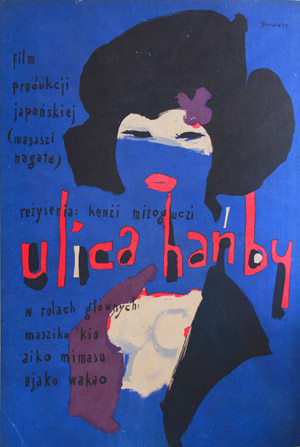

Fig. 32. Waldemar Swierzy, film poster, Ulica Hanby, 1959

Poster work became so plentiful that the artist Waldemar Swierzy (Fig. 32), recounting his career, said, “There were years when I was making a poster every week, and often had to decline commissions.”

The daily newspaper Zycie Warszawy held a yearly readers’ poll for the best posters of each month and for the overall best poster of the year. The leading poster artists became nationally famous and were recognizable to ordinary citizens by their individual styles. In a preface to the catalogue of the 8th Biennale in 1978, Jiri Hlusicka wrote “The graphic realizations and designs exhibited here are not a mere response to political and social subjects, they are crucial to the hopes of mankind and endeavor towards a better world.”

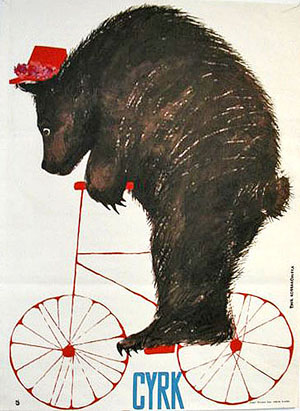

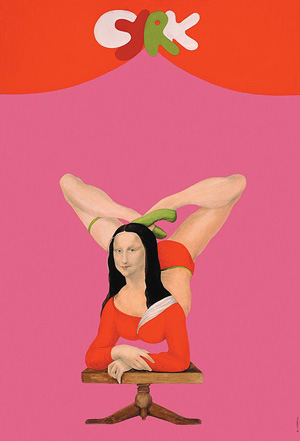

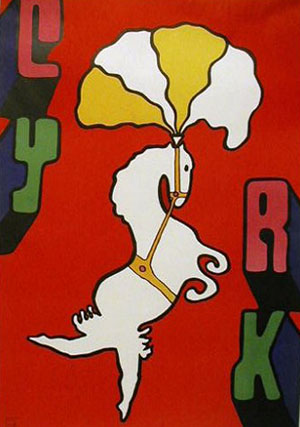

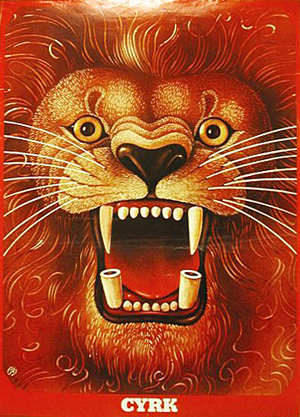

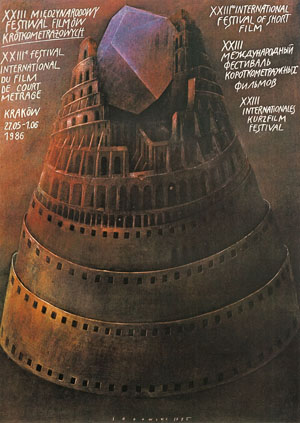

CYRK, the First Wave of International Recognition

Poland became an autonomous Communist country in the early 1960s. The Polish agency called ZPR (Zjednoczone Przedsiębiorstwa Rozrywkowe) or United Entertainment Enterprises was placed in charge of improving and modernizing the public image of state-sponsored “Cyrk” (circus) entertainment. Rather than using traditional advertising methods to accomplish that, ZPR commissioned and permitted leading artists to create personal and responsive designs for posters. Without the restriction of having to portray the circus using literal realism, artists were free to express their own interpretations of Cyrk. The style varied by artist, but in general was similar to commercial illustration being done during the 1950s and 1960s in Europe and the United States: playful and in a cartoon-like abstraction, with loose, painterly brushwork or with painted cut paper and collaged textures. Vividly colorful designs reflected a Polish folk-art heritage.

The resulting work received wide exposure through poster competitions that attracted international entries and achieved global recognition in the field of graphic design. Cyrk posters (like most posters) used a simple primary image to send an instant message. Often it was a circus performer, a figure with a prop, or small grouping of figures in a stylized action. Polish artists complemented the images with playful typography or hand lettering integrated into the design, which typically read only the single word, CYRK.

Fig. 33. Ewa Kossakowska, circus poster, 1962

Fig. 34. Jerzy Srokowski, circus poster, 1963

Fig. 35. Maciej Urbaniec, circus poster, 1970

Fig. 36. Antoni Cetnarowski, circus poster, 1971

Fig. 37. Jan Mlodozeniec, circus poster, 1971

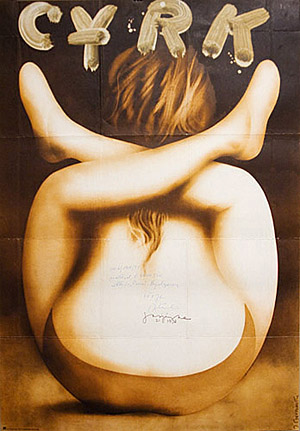

Fig. 38, 39. Jerzy Czerniawski, circus poster and detail, 1975

Censorship

While the graphic arts were supported by the state, all posters were subjected to review through official channels that supervised content, printing and publishing. State-authorized printing companies would run test sheets of a poster before the final printing, and one of these would be presented to censors. The poster would be hand-signed by the censor, if approved, and then retained on file (Figures 38, 39). Censors saw the Cyrk posters as being generally harmless but some designs containing subtle critical commentary about the state were passed through unnoticed. Two examples are shown below.

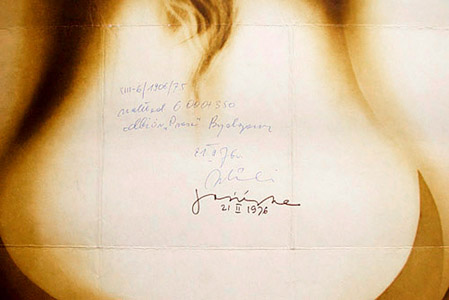

Fig. 40. Andrzej Pagowski, circus poster, 1979

The scrawny, powerless elephant represents the USSR as it foolishly wears the defiantly beautiful ears of the Polish nation. Use of the English word connotes a pro-western attitude.

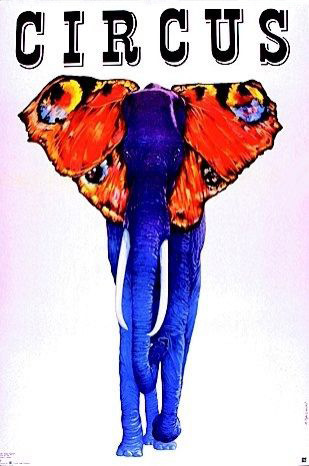

Fig. 41. Rafal Olbinski, circus poster, 1980

The lion is Poland. Tamed but still with sharp teeth, it roars and threatens an attack where its fangs will lock into a death hold on the corrupt and repressive state.

With popularity and greater demand, poster designs produced initially in small quantities for local display came to be reproduced in second and third printings in larger quantities for international distribution through retailers and mail order. The audience was no longer just those who saw the posters pasted onto walls in Polish cities, it had become an appreciative international mix of college students, middle-class professionals, intellectuals, young couples, and artists and designers from all over the world who appreciated and wanted to live with these images every day. The new commercial prints were large, typically about three feet in height, and reasonably well produced.

The Cyrk posters marked the beginning of an international poster craze that took place in the 1960s and 1970s and came to include not only Polish designs but also poster art from all cultures and eras. Posters became popular consumer items for wall decor and for expressing the personal tastes and interests of their buyers. The French designs by Cheret, Toulouse-Lautrec and others, the Art Nouveau advertising posters of Alphonse Mucha, cafe posters from Austria, reproductions of surrealist works by Salvatore Dali and René Magritte, and posters originally created to promote art gallery shows and museum exhibitions were all being reproduced for retail sales, as were protest posters and posters promoting social causes. Rock bands and music venues commissioned young artists to design posters for concerts and tours, and jazz and classical concert promoters and record companies used posters as marketing tools, hiring experienced graphic artists to create striking designs. There was a poster renaissance in the late 1960s and 1970s—a rebirth of interest in poster creation and avid collecting similar to what took place just before and just after the turn of the 20th century, and Polish works were a significant part of that.

1980s-1990s: A Darker Art

The cheerful, colorful Cyrk posters belied an oppressive economic system not adequately providing for its citizens, and the 1970s were fraught with civil unrest and worker’s strikes. The Polish Communist Party’s failing policies engendered food and housing shortages as well as massive unemployment. In the 1980s, the national mood was reflected in Polish posters, making them a darker art: psychologically expressive, sometimes shocking in their frank sexuality, grotesque or fantastic surrealism and intimations of despair.

In theater or film posters, literal representations of plot or depiction of characters were not the Polish way. Since Trepkowski’s groundbreaking works in the late 1940s, Polish designers typically used more oblique means of sending messages: symbolism, metaphor and analogy. Creative imagery supports the practical purpose of the design but does so in a complex and engaging, non-literal way.

— Symbolism provides understanding based on common cultural iconography.

— Metaphor allows for the development of connective conceptual relationships. Visual and verbal ideas support each other, and metaphors ask viewers to engage with the art in order to tease out meaning.

— Analogy provides two ideas that support each other and thereby instill a more layered understanding of meaning.

These methods are perfect tools for poster creation, where visuals have to be simple enough to attract attention and allow almost instant comprehension of purpose, yet produce messages that are richer than representations of literal content. This intellectual challenge, when combined with a powerful aesthetic, produces a lasting impact on viewers. Posters, like all art, are deepened in their effect when more time is spent in their presence, and, historically, Polish poster artists have approached their medium with the intention of creating work that engages and holds the viewer.

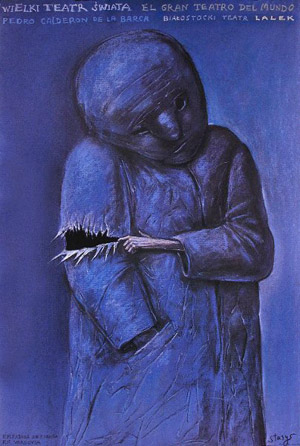

Fig. 42. Stasys Eidrigevicius, theater poster, The Great Theater of the World, 1989

In this 1635 play by Pedro de la Barca, God has created the play that is the world. A King has power, a merchant has riches and a peasant suffers, but they are all actors directed by their creator and their performances are judged, rewarded or punished. Eidrigevicius paints an anonymous, symbolic character that has torn at his clothing—a biblical expression of grief—because God’s manipulations have shown him the truth about himself.

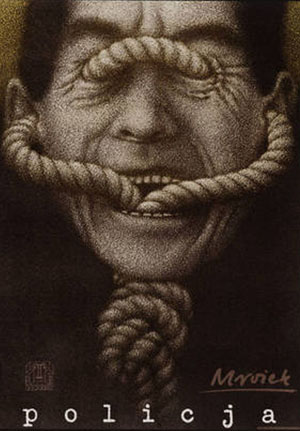

Fig. 43. Mieczyslaw Gorowski, theater poster, Police, 1982

In Mieczyslaw Gorowski's painting a rope is used as a metaphor and is given frightening animation. Its disturbing insinuation into the orifices of the head show the restriction and corruption of all the senses, while it also chokes the throat of the character. Police was a response by playwright Slawomir Mrozek to the imposition of martial law in December of 1981 that was meant to suppress the Solidarity movement. Gorowski’s character is both police and citizenry, oppressor and victim. The rope represents the punishing binding that is communist repression of freedom.

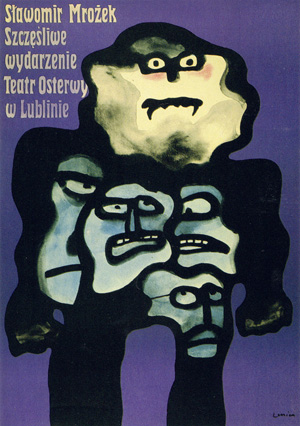

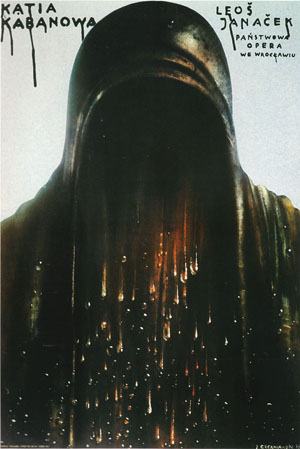

Below are further examples of posters that were created for Polish theater and opera productions through the 1970s and 1980s. The artists who designed and illustrated these and the film posters that follow represent a sampling of the extraordinary talent and imagination that flowed into the genre from the root source of the post-war era masters.

Fig. 44. Jan Lenica, theater poster, The Fortunate Event, 1973

Fig. 45. Jerzy Czerniawski, opera poster, Katia Kababowa, 1978

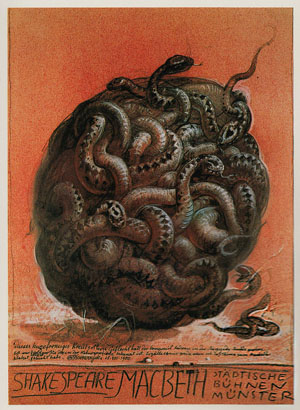

Fig. 46. Franciszek Starowieyski, theater poster, Macbeth, 1980

Fig. 47. Henryk Tomaszewski, theater poster, Mannequins, 1985

Fig. 48. Wiktor Sadowski, theater poster, White Wedding, 1986

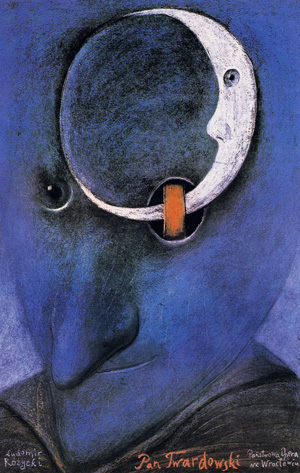

Fig. 49. Stasys Eidrigevicius, opera poster, Pan Twardowski, 1987

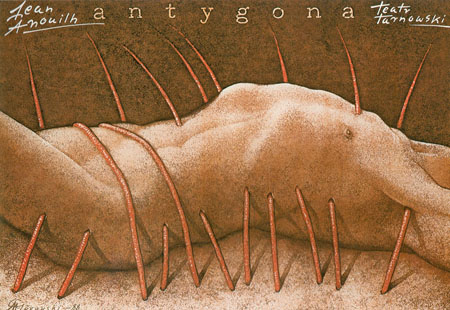

Fig. 50. Mieczyslaw Gorowski, theater poster, Antigone, 1988

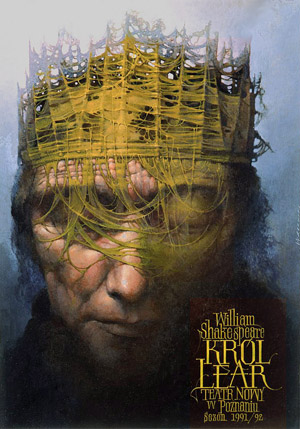

Fig. 51. Wieslaw Walkuski, theater poster, King Lear, 1991

For the Polish people, American and European films played an important role in the understanding that there were alternatives to life under Soviet-style communism. American films especially, were viewed and enjoyed by Poles who had never known a different way of life. Polish fashion, music, and social behaviors were becoming so influenced by what moviegoers saw that from the late 1940s to the late 1950s the state prohibited the exhibition of American films. Regardless, movies drifted steadily into the country, and theater owners risked showing them. In fact the film showings were popular with everyone, including political leaders and party bureaucrats who secretly attended them.

Beginning as early as the 1950s “Graphic artists found in the creation of posters the possibility of ‘smuggling’ in world trends and intellectual values [a new style] that was addressing the audience with a language of contemporary vividness involving concise synthesis reflecting more the film’s atmosphere than its content.”[8]

By the 1960s, more foreign films were being imported and lawfully distributed, and Polish poster artists were commissioned to create their own subjective treatments of the films’ content, providing Polish interpretations rather than American or European ones.

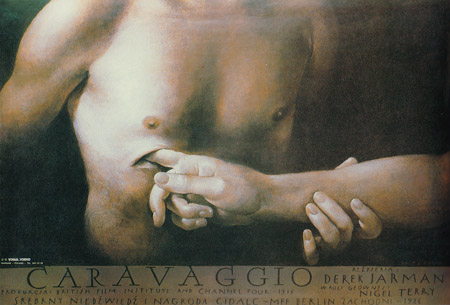

Fig. 52. Wieslaw Walkuski, film poster, Caravaggio, 1990

A poster by Wieslaw Walkuski for the film Caravaggio demonstrates the Polish approach. Here, Walkuski paints an image of a male torso with a gaping bloodless wound shown being probed by a man’s finger, an act that is being guided by another hand. At first, a viewer perceives that the wounded man is assisting in the penetration himself, but a closer look reveals that the guiding hand is gentle, delicate and feminine. Three people are involved, and the act of violation is representative of the relationship between the painter Caravaggio and two of his lovers, one male and one female, that are part of the film’s narrative.

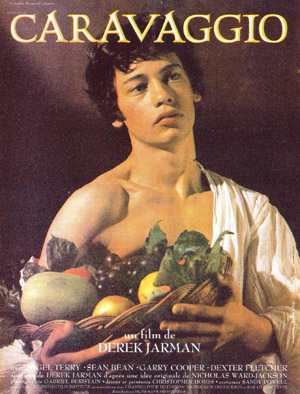

Fig. 53. Film poster (France), Caravaggio, 1986

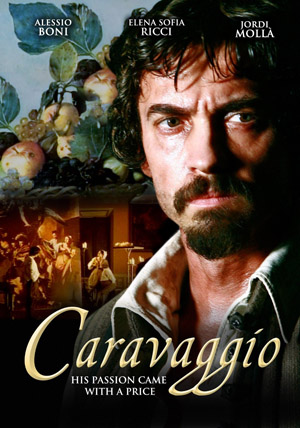

Fig. 54. Film poster (USA), Caravaggio, 1986

Contrast the interpretive Polish design with two commercial versions (Figures 53 and 54) distributed with the film—one French and the other American—that show no attempt at communicating content. There is no question as to which version is the most compelling, thought provoking and artful. The difference between art and advertising is obvious.

Note, too, that in most Polish posters there is an integration of text and image within the art itself through the use of expressive hand lettering rather than typesetting, making the communication of textual information interpretive as well.

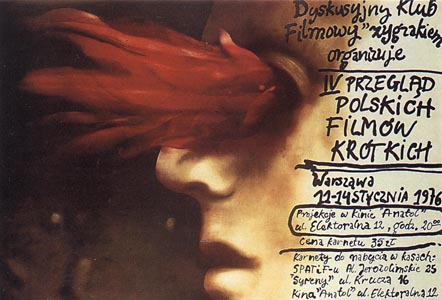

Fig. 55. Jerzy Czerniawski, poster for film club, 1976

Fig. 56. Wiktor Sadowski, poster for film festival, 1985

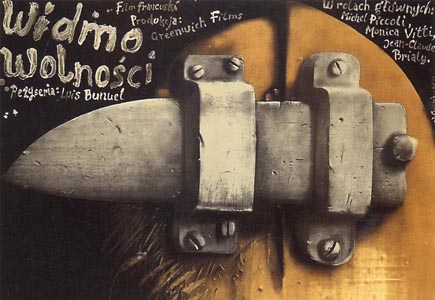

Fig. 57. Jerzy Czerniawski, film poster, Le Fantôme de la Liberté, 1975

Fig. 58. Wieslaw Walkuski, film poster, Bagdad Café, 1988

In his foreword to the book, Masters of Polish Poster Art, the design historian Steven Heller wrote:

“It is ironic that a nation whose government was under the thumb of ideology, and whose citizens were restricted by dictates and decrees, could produce a national graphic style of such high quality and integrity based on individuality. To Americans the Polish poster was the epitome of expressive and stylistic freedom. While in the United States, graphic artists and designers were free to say virtually anything in print, if they really wanted to earn livings, even the most renowned had to be slaves to their clients. American business imposed styles and fashions that would sell products in the competitive marketplace. Deviations from these conventions were few; experimentation was suspect. Which isn’t to say that [all] American design was uninspired… but the Polish poster was pure poetry, seemingly unfettered by agendas of state… Could it be that repression produces the best art? Are artists enlivened by the idea that visual language can subvert the tunnel vision of the state? …that either the authorities were looking the other way or artists were truly brilliant subversives? Americans understood, of course, that these images mostly for cultural events did not have to sell to specific demographically identified consumer groups, or please the chairmen of major corporations, or appeal to the special interests. But they did have to transcend (and fool) a regime that was suspicious of individual expression.”[9]

In the 1990s, after the era of state sponsorship for poster creation, film posters gradually took on the commercial appearance of those produced by the originating movie studios. Polish film distributors believed these to be done in a more effective international contemporary style that would attract ticket buyers. Polish film societies and theatrical producers, however, continued to use non-literal, expressive and conceptual designs for promoting events and still do so today, simply because this kind of work is so much a proud reflection of the national artistic spirit.

Fig. 59. Jerzy Janiszewski, logo for Solidarity movement, 1980

In 1980 a strike by workers at the Gdansk shipyards led by Lech Walesa, a former electrician, marked the beginning of the final stage of Poland’s struggle for independence. The strike inspired similar actions across the country, with Walesa seen as leader. The government reluctantly negotiated an agreement that allowed workers to form a union that was independent of communist governance. Calling itself Solidarity, the union became the driving force that led to free parliamentary elections and to finally unseating the long-established communist regime. In 1990 Lech Walesa was elected president of a free and independent Poland.

The logo for the Solidarity movement was designed, naturally, by a poster artist, Jerzy Janiszewski. It is a powerful example of hand lettering, with the letters forming the visual impression of a line of marching workers linked together and carrying a flag. It was only fitting that this free and expressive design, so typical of the symbolic and metaphorical works created by Polish poster artists, would become an icon representing the realization of the Polish dream of democratic self-rule.

“In the 1980s many Polish artists began visiting and emigrating to the United States. Most were the scions of the great poster masters and many came with styles that emulated these venerable few. Within a short time, the Polish style was curiously integrated into aspects of American graphic art and design. And today it is accurate to say that American illustration is an amalgam of our own indigenous and Eastern European components. But whenever an American wants to be inspired by great work… [they] still admiringly look out to Poland, where the masterpieces of poster design reside.”[9] Ibid.

Posters are an art form that has never waned in popularity with either its creators or its audiences throughout the history of printed communication. It is an art that is part of the landscape of our cities, and, even in this digital age of electronic devices and pop-up web ads, street posters are still seen by millions. International poster competitions take place each year, and winners are honored with awards and see their works published in graphic design trade magazines, compendium books and “year’s best” design publications. Works by distinguished Polish poster artists are exhibited in museums and galleries, and there are several Polish websites that offer reproductions and preserved original prints for sale.

The art of the poster, its essence, is in its connection to the populace, but the popularity and commercial purpose of posters should not diminish their importance as art. In the poster, the varied disciplines of communication design, advertising, fine art, graphic design, typographic design and illustration coalesce into a primary form of expression—a universal artwork.

RESOURCES

[1] Info-Poland.buffalo.edu/gallerymap.shtml —Polish Academic Information Center website; Ed., Dr. Peter K. Gessner, Ph.D., University at Buffalo, SUNY and Jagiellonian University, Cracow, Poland.

[2] Millie, Elena and Zbigniew Kantorosinski. The Polish Poster: From Young Poland through the Second World War; pdf publication. Library of Congress, Washington, DC: 1993.

[3] Fox, Frank. Magazine article in The World and I, A Chronicle of Our Changing Era, Washington Times Corp., May 1990.

[4] Boczar, Danuta A. Vol. 44, No. 1, The Poster, Spring 1984.

[5] Lenica, Jan. The Polish Film Poster, ed. Tadeusz Kowalski, Filmova Agencja Wydawnicsa, Warsaw, 1957.

[6] Fox, Frank. Catalog essay for the exhibition Poland and the American West, Autry Museum of Western Heritage, October 16, 1999 through January 30, 2000.

[7] Schubert, Zdaislaw. The Polish Poster, Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza, Warsaw, 1979.

[8] Szpor-Weglarska, Anna. Foreword to the publication 100th Anniversary of the Cinema in Poland, 1896-1996. Gallery Plakatu, Krakow, 1996.

[9] Heller, Steven. Foreword to Masters of Polish Poster Art, ed. Dydo, Krzysztof, Bielsko-Biala, Buffi, 1995.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

– Aulich, James and Sylvestrova, Marta. Political Posters in Central and Eastern Europe, 1945-95. Manchester University Press, 2000.

– Czestochowski, Joseph (Ed.). Contemporary Polish Posters in Full Color. Dover Books, 1979.

– Davies, Norman. Heart of Europe: A Short History of Poland, 1984.

– Dydo, Krzysztof. Masters of Polish Poster Art. Bielsko-Biala, Buffi, 1995.

– Dydo, Krzysztof. Polish Film Poster/100th Anniversary of the Cinema in Poland 1896-1996, 1996.

– Fox, Frank. Polish Poster: Combat on Paper, 1960-1990, Katonah Museum of Art, 1996.

– Wazniewski, Jerski. Plakat Polski (Polish Art Posters), WAG (Wydawnictwo Artystyczno-Graficzne), 1972.

– Wettig, Gerhard. Stalin and the Cold War in Europe, Rowman & Littlefield, 2008.

LINKS to Websites Featuring Polish Poster Art:

cracowpostergallery.com/index2.php

moma.org/visit/calendar/exhibitions/956

pigasus-gallery.de/polish-poster.htm