Artists assume the responsibility to make us feel, question, and re-evaluate. Illustration is often associated with depictions of everyday life, but is not solely confined to do so through realism. Magical elements can broaden the viewer’s mind to arrive at conclusions and introspections they may have not otherwise found if all the information and rhetoric were plainly given. The Spanish painter Francisco Goya (1746-1828), wrote to the Academy of Art in the 1790s to petition for a curricular reform that would allow artists, in addition to honing skills in rendering, to also look inward to access imagination and self-expression. He said this “transcendence” could occur when the artist’s work belongs to the “realm of ideas,” and although he describes admiration and appreciation for when artists achieve realism, he said in the letter, “he who departs from it (imitation) entirely will not be left without deserving some esteem for having had exposed to the eye forms and attitudes that until now only exist in the human mind, obscured and confused by a lack of enlightenment, or heated by unbridled passion.”[1] Goya saw the importance of freedom and integrity to explore subject matters within reality and imagination and deemed both worthy of artistic importance and relevance.

Magical Realism is a fairly new term, coined in 1925 by Franz Roh (1890-1965) a German art critic. At this time, it was not widely used and was not specific to any art movement. In the 1940s in Latin America, it was used as a literary genre. Magical Realism depicts a world with a familiarity that makes it relatable so that the magic of the place is then perceived and accepted as normal.[2] Goya, although living well before the phrase Magical Realism was used, is an early representation of the blurring of a distinction between reality and fiction.

By using fantastical elements, Goya showed corruption within the Spanish aristocracy, analogized pain and suffering, indulged in his imagination, and depicted the lives of the non-elite. Goya’s success in personal exploration is something Andrea Kowch (American, b.1986), Amy Cutler (American, b.1974), and Shaun Tan (Australian, b.1974), three illustrators in the modern day, are known for within their practices and styles. These three illustrators, along with Goya, utilize a magical reality to relate to everyday life, to infuse symbolism, to communicate, and to deepen the access to their work. Through the comparisons of these artists to that of Goya, we see how the illustrator can create a gateway to their fully developed inner worlds, inviting the viewer to find their connection to the possible meanings of the work.

Illustration and the Neglected Scenes of Everyday Life

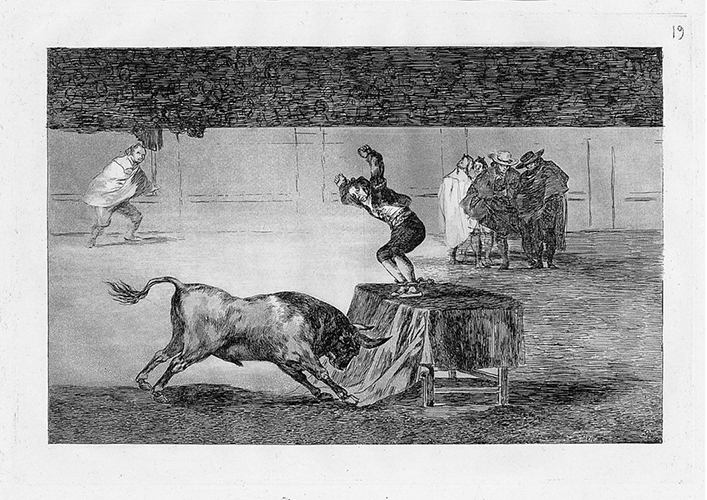

Fig. 1. Francisco Goya, Plate No. 19: [Temeridad de Martincho en la plaza de Zaragoza] Otra locura suya en la misma plaza ([Boldness of Martincho in the Bullring at Saragossa] Another Madness of His in the Same Bullring), ca.1816.

Living within the instability of the Spanish Inquisition, Goya, who was once a very respected court painter, was removed from court and returned to painting tapestries. This was a common fate for Spanish court artists in 1790. This demotion re-immersed Goya within the lives of the non-elite, inspiring him to work beyond the scope of commissioned art for royalty and the Church. King Charles IV deemed these tapestries “rural and comic” with their newly satirical tone and depictions of “wily women, men who tempt fate…children who illustrate the have and have nots of society.”[3] Goya, now guided by his own artistic integrity, illustrated “bullfights, shipwrecks, attacks by robbers” as scenes from the life that was considered unimportant and not aesthetically desirable.[4] As shown in Figure 1, Goya focuses the composition of the etching around the bullfight; those who paid to see it, the elite, are blurred in the background, focusing the viewer on the performer and the bull. Goya’s newfound passion directs the focus of art away from the royalty and the Church to that of the common people.

Fig. 2. Andrea Kowch, Marsh Hare, 2010.

For Andrea Kowch, Amy Cutler, and Shaun Tan, everyday life uniquely informs their work in the modern day. Andrea Kowch’s work is described as “resplendent imagery, with an overall ambiance of frozen moments in time.”[5] Kowch finds inspiration in the landscapes of the Midwest and the history of Americana. She depicts the forgotten world of domestic women and the daily grind of farmers. In Figure 2, her painting Marsh Hare shows two women in a wild environment, surrounded by crows and embracing hares, not recognized as predators, but as part of the natural and animalistic world. Kowch is inspired by characters that are immersed in nature, relying upon it for their livelihood and appreciating it for its wonder. She is quoted saying, “If my work succeeds at all in paying any sort of tribute to these people and their way of life, and subsequently arouses others to take notice and pay their respects just the same, then I know I’ve done well in that aspect of my mission.”[6] In contrast to Goya, Kowch has the opportunity to see her work received by those who can especially connect with the rural way of life she represents while also magically enhancing it. For example, she said, “farmers are the ones actually living and experiencing most of the environments and scenes that I paint. Listening to them identifying with the settings, tasks, and range of emotions expressed throughout the scenes, and finding a level of strange solace in their familiarity, is really special for me.”[7] The relatability to the rural and domestic worlds Kowch’s paintings are inspired from, creates a truly successful render within a magical reality.

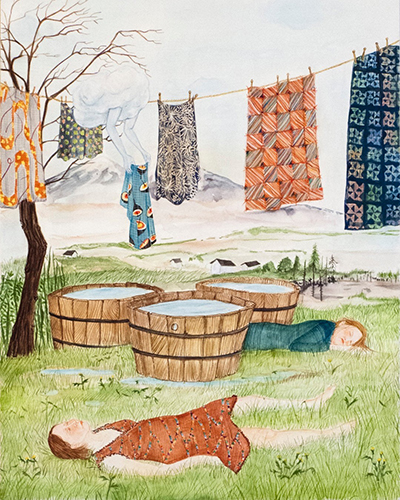

Fig. 3. Amy Cutler, Overcast, 2012.

Amy Cutler uses the connection to everyday life as a way to analogize her fantastical portrayals of womanhood. Her style is described as a “secret world” where “salt-of-the-earth women work hard, solemnly powering through their fantastical chores with thankless determination.”[8] In Figure 3, “Overcast” is an illustration where women are asleep within the scene of their daily chores, in this case laundry. The viewer can connect to this piece, having inevitably wished at some point they could sleep while chores and responsibilities were being magically done for them, but Cutler shows this as a possible reality, giving these women a break from their daily duties. “Overcast” is belonging to the “realm of ideas” in its strangeness and impossibility but obviously inspired by the exhaustion that comes with a hard day’s work, the grind of domestic life (particularly for women), and the hope to avoid responsibilities as a result of that exhaustion. The tangible inspirations from everyday life and struggles within the female experience, provide Cutler with the research that informs her work. Cutler is an observer of the world around her, calling the subway a “great place to shop for features” that inform her character design.[9] Cutler describes her relationship to facial features by saying, “the face always leads the way to the posture, costume, and ornamentation. It’s a dance. Sometimes the work will hang on my studio wall as floating heads until I can imagine what each character is trying to express.”[10] Goya and Cutler shared in the use of real life and their unique perspective within society as research to guide and enhance their fantastical portrayals.

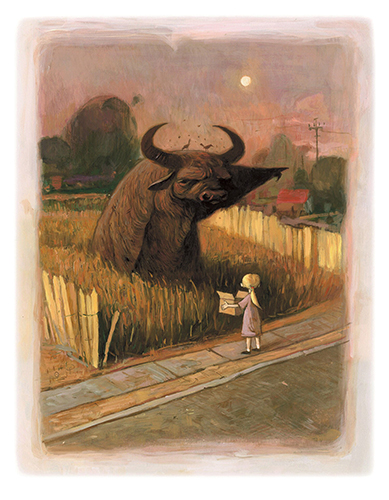

Fig. 4. Shaun Tan, Illustration from Rules of Summer (Sydney, Australia: Lothian Children’s Books, 2013).

Shaun Tan draws inspiration from his childhood—beckoning the viewer to recall their own experience with nostalgia. Figure 4 is one of the illustrations from Tan’s book, Rules of Summer (2013). It features more fantastical elements, but the tone of the boyish play roaming in the fields in summertime is what helps the viewer embrace the fantasy as common place within this world. Tan has a talent for rendering, combined with a talent to skew reality. Using Figure 4 as an example, the fields of wheat and the environment are painted in a way to look like this place could exist, causing the fantastical subject matter to be more readily embraced by the viewer. Goya in no way discredited realism and the artist’s ability to accurately portray, but saw it as an opportunity to combine skill with imagination to fully evolve the artist’s ability to create.

Goya, Kowch, Cutler, and Tan use everyday life and memories within their human experience as the research needed to distort, exaggerate, and skew within their magical worlds. What may seem to others as mundane and ordinary, to them, is what informs their magical realties.

Permission to Speak Freely: The Role of Symbolism

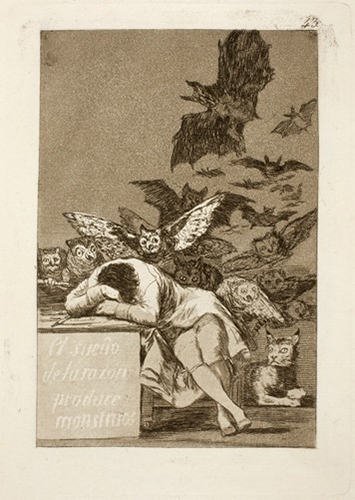

Fig. 5. Francisco Goya, El Sueño de la razón produce monstruos’ (The dream of reason produces monsters), Capricho 43, 1797-1798.

In 1790, accompanying the “Sueños” and “Los Caprichos” series of etchings, Goya began to add captions to his works as a way to add “overt commentary.”[11] His work at this time (figs. 5 and 6) was described as “increasingly intimate and experimental.” Most of Goya’s criticisms were directed towards the Spanish aristocracy and the atmosphere of devastation during the Spanish inquisition in Madrid. “Los Caprichos,” in particular, was created in “wartime Madrid” and thought to be “relentlessly tragic” and “an extended meditation on the devastation of war, imagining the atrocity of conflicts raging beyond Madrid”.[12] The frustrations expressed in “Los Caprichos,” were not only political but philosophical. For example, in Figure 6, the imagery of witches disguised as donkeys (disguised as bedside nurses) analogizes that people are not always what they seem and may be hiding their darkness. Goya “gave form to a world where ignorance and cruelty have displaced all virtue,” which he further explores in the etching “Sleep of Reason,” and the bulk of the work he created later in his life.[13] In “Sleep of Reason,” (fig. 5) part of the caption reads, “Fantasy abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters,” implying the cause of “producing monsters,” or instilling corruption, is the forsake of reason.

Fig. 6. Francisco Goya, De que mal morirá? (Of what ill will he die?), Capricho 40, 1797-1798.

Goya’s fervor for reform extended beyond that of his criticisms of the Spanish government. He wrote to several patrons of numerous Academies of Art Education imploring them to let their students indulge in self-expression, further away from “tired precepts and academic traditions.”[14] This petition for curricular reform was inspired by his reliance upon his imagination as a way to understand and critique the world around him that would otherwise have “no place in commissioned works, in which whimsy (capriche) and invention have no room to grow.”[15]

Kowch, Cutler, and Tan use symbolism to speak freely, feeling still a veil for their specific inspirations, not to hide, but to broaden the chance of multiple interpretations. For example, wind is a reoccurring symbol for movement and transformation in Kowch’s work. In Figure 7, it has such a dramatic presence that it almost transforms the landscape and acts as subject matter in and of itself. The role of symbolism is not only for the experience of the viewer but for Kowch’s relationship to the work. She has said that the symbolism infused in the work “has to carry a certain power and seductive mystery about it, make me ponder, and grip my soul and excite my spirit beyond measure.”[16] Symbolism and its mysteriousness fuel the motive and passion behind her work, strengthening her connection to it. Similarly, Goya became so emotionally attached and proud of his later work and etchings that he left the majority of that work in his will to his son.

Fig. 7. Andrea Kowch, No Turning Back, 2008.

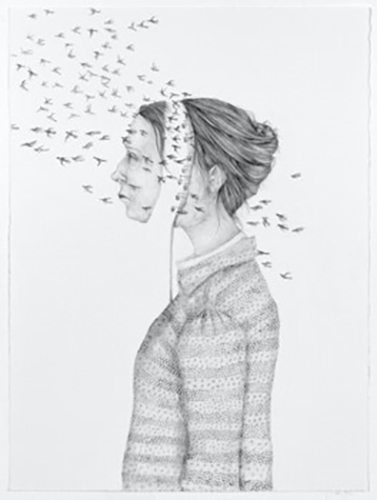

Similar to Kowch and her motif of wind, Cutler often analogizes migration. For example, the reoccurring presence of birds in her work, which she says, “represents migrating thoughts, which travel in and out of the head” (fig. 8). Many of her characters are usually traveling by foot and carrying large parcels which also inform the feeling of migration. She says, “Fabric bundles or hobo sacks are also prevalent in my work and function as a symbol of transition while concealing or protecting something.”[17] Cutler’s use of symbols in a repetitious way, helps viewers recognize the artist’s distinct style and common overarching themes. Similarly, Goya’s fantastical work became unmistakable with his recurring use of witches, ghouls, animals, and monsters, along with his innovations in his etching and lithograph techniques themselves.

Fig. 8. Amy Cutler, Egress, 2018.

Tan tackles symbolism as a vehicle for expression to counteract or aid his introverted nature. He often describes when he is in the early stages of writing, that he pretends he is telling the story to his brother, using that scenario to access his thoughts openly. The artist succinctly describes this when saying, “when emotion is attached to something that is completely outside of experience, it makes you examine it, as though it has no wrapper on it.”[18] Goya, while struggling with his worsening deafness, used art as a way to communicate and absorb the world around him. Solitude is often associated with the life of the artist, but as for Tan and Goya, it is what communicates and connects them.

Symbolism, as it pertains to Goya, Kowch, Cutler and Tan’s illustrations, re-emphasizes the sobering consciousness that fuels the metaphoric imagery and connects the viewer to a plentitude of meanings and observations.

Access and the Ongoing Conversation

In the last decade of his life, Goya drew constantly. He utilized mostly “pencil, chalk, pen and ink, brush and ink, and crayon” and with his increasing hearing loss, used illustrating as a way to “hear” the world around him and relay his “stream of consciousness.”[19] Amy Cutler talks about art as communication, noting, “Ambiguity makes the work more accessible” for both viewer and artist because “as time passes the meaning also changes for me… If I was to fill in all the details the image becomes static and harder to enter.”[20] This relationship with her work expands into a place of limitless interpretations and possibilities that continue beyond the moment of creating, into a relationship that persists and changes with time. The deepness of the experience that the artist can have with their work, transforms the creative experience into a relationship, as Cutler describes, and as a language and way of life and survival, as was for Goya.

Kowch and Tan share a similar intimacy with their work, Kowch seeing it as “diary” of her “life’s journey, in visual, allegorical form.”[21] Tan uses his work as a way to re-examine the past, especially as it pertains to the immigrant experience, both from his own life and also his ongoing frustrations with the political climate surrounding immigration. Figure 9 is an illustration from Tan’s “Tales from Outer Suburbia” where a water buffalo points the child in the right direction without saying where to go or how to get there. There is a fear of the unknown that Tan explores in his narrative of immigration but eludes that with the help of others, one can be “surprised, relieved, and delighted” and what the unknown can contain.[22] Isolation and fear of uncharted territory are themes Tan feels he can explore through his work as a means to process the full intensity of these emotions.

Fig. 9. Shaun Tan, The Water Buffalo, 2006.

The Transcendence

Goya suggested that art belonging to the “realm of ideas” is brought forth from an “enlightenment” and a passion that can come from self-expression and the strengthening of an artist’s intimacy with their creativity. Like Goya, some illustrators and artists rely on commissioned and product-based work. The need for self-expression, escapism, and introspection that Magical Realism can provide, gives illustrators like Cutler, Kowch, and Tan endless possibilities to analogize their personal experiences. Illustrators’ indulgence of their own creativity is more commonplace in the creative processes today, stemming from the freedom to choose content, narrative, and style, whereas Goya was before his time in the conceptuality of this freedom. He is an early pioneer of new ways of storytelling and expression, and so fervently believed in and petitioned for the evolution of the artist as “inventor” and not a “copyist.”[23]

1. Janis A. Tomlinson, Goya; A Portrait of the Artist. (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2020), 252.

2. Lois Parkinson Zamora and Wendy B. Faris, eds., Magical Realism: Theory, History, Community. (London: Duke University Press, 1995), 15-17.

3. Tomlinson, Goya; A Portrait of the Artist, 174.

4. Ibid., 195.

5. Eclectix Art. “Andrea Kowch, Eclectix Interview 60.” October 28, 2015. Updated September 27, 2019. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://medium.com/@eclectixp/andrea-kowch-eclectix-interview-607bb7099382f0

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Kristin Farr, “Amy Cutler; No frills.” Juxtapoz Magazine. June 21, 2017. Accessed October 17, 2020. https://www.juxtapoz.com/news/magazine/features/amy-cutler-no-frills/.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. Tomlinson, Goya; A Portrait of the Artist, 205.

12. Ibid., 26.

13. Ibid., 27.

14. Ibid., 193.

15. Ibid.

16. Eclectix Art, “Andrea Kowch, Eclectix Interview 60.”

17. Farr, “Amy Cutler; No frills.”

18. Robyn Henderson, “Meet the Artist: An Interview with Shaun Tan, ” Iowa Review. December 7, 2016. Accessed October 9, 2020. https://iowareview.org/blog/meet-artist-interview-shaun-tan

19. Tomlinson, Goya; A Portrait of the Artist, 206.

20. Kristin Racaniello, “Amy Cutler: Using Magical Materiality as Feminist Critique,” The Brooklyn Rail. March 12, 2019. Accessed October 17, 2020. https://brooklynrail.org/2019/03/criticspage/Amy-Cutler-Using-Magical-Materiality-as-Feminist-Critique

21. Eclectix Art, “Andrea Kowch, Eclectix Interview 60.”

22. Shaun Tan, Tales from Outer Suburbia (New York: Arthur A. Levine Books, 2008), 6.

23. Tomlinson, Goya; A Portrait of the Artist, 251.