Description

The term tattoo originates from the Tahitian word tatau meaning “to mark.” It was thought that the earliest examples of tattoos appeared on female Egyptian mummies dating 2000 B.C. However, in 1991 the famous “Iceman,” carbon-dated at around 5,200 years old, was discovered near the Italian-Austrian border. His lower back, ankles, knees, and a foot were marked with a series of small lines, made by rubbing powdered charcoal into vertical cuts. X-rays of the frozen remains led the researchers to the conclusion that the tattoos were done for medical reasons. Since then, humans have marked their bodies to indicate one’s role in society, religious beliefs, clan, or his/her rite of passage.

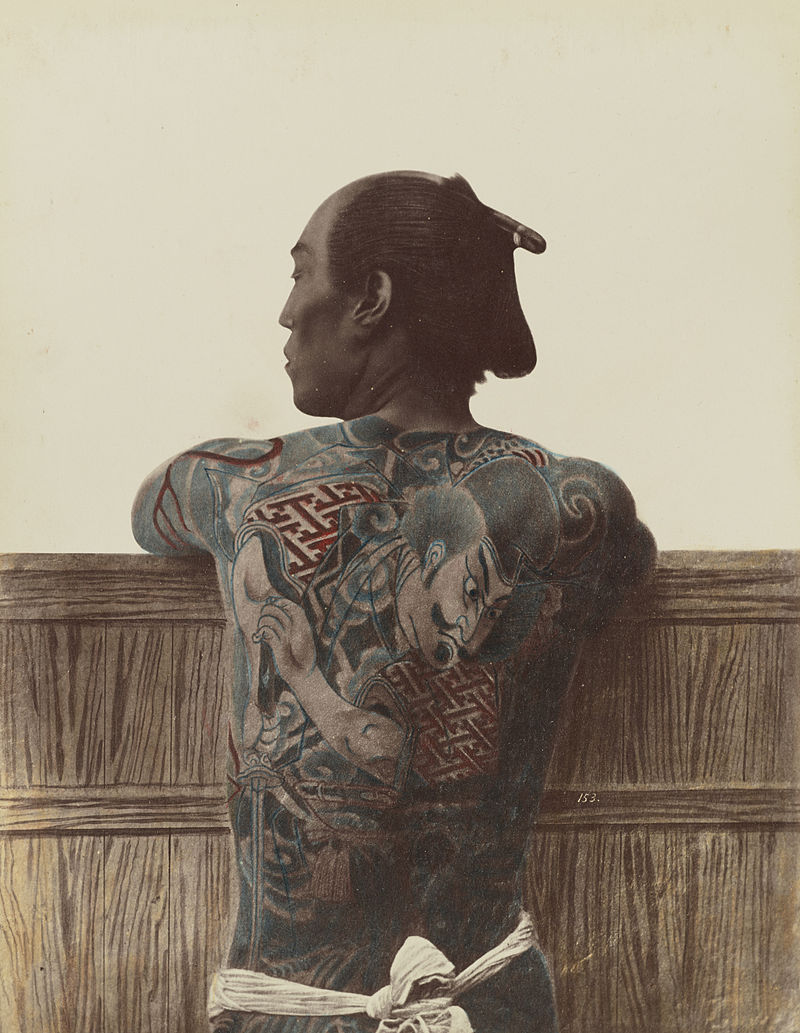

Kimbei or Stillfried, Japanese Body Suit, ca.1875

Two cultures, in particular, have been influential in the evolution of a tattoo becoming an art form. Since around the 5th century B.C., the Japanese have created exquisite designs. Repressive laws restricted the lower class from wearing lavish kimonos that were meant for royalty and the elite. Outraged merchants and the lower classes rebelled by wearing tattooed body suits, illustrations that began at the neck and extended to the elbow and above the knee. Wearers would hide these elaborate decorations beneath their clothing. Viewing the practice as subversive, the government outlawed tattoos in 1870 as it entered a new era of international relationships. As a result, tattooists went underground where the art flourished as an expression of the wearer's inner longings and impulses.

Unidentified Maori Man

In New Zealand, a Maori leader received a moko, or personal facial tattoo. A moko differs from a tattoo because the design is carved into the skin rather than punctured. Originally, island practitioners used a bone chisel for working their patterns into the skin, a painful process, and stained the incisions with ink. These designs marked the wearer’s transition into adulthood, and identified his status and rank. Today, Te Uhi a Mataora is a collective of ta moko artists dedicated to making ta moko a living art form. Information on several artists can be found on the Museum of New Zealand website.

At the turn-of-the century, tattoos were found on soldiers or circus ladies in America. It was not until the 1960s that tattooing for art's sake became popular. During the 1970s, traditionally trained artists began experimenting with tattoos which resulted in fresh imagery and drawing techniques for the industry. Advances in electric needle guns and pigments has allowed tattooists to reach new plateaus through the variety of new inks and ability to execute intricate details. Today, the tattoo profession falls into two business models: the "tattoo parlor” and the "tattoo art studio." The fine art tattoo studio draws clients looking for shop for unique body art that reflects their personal style.

Across the United States, Canada, and Europe, tattoo designs have become the subject of museum and gallery art shows. In 1989, Esquire magazine reported, "Serious artists...are joining the ranks of tattooers and their designs are being exhibited in museums and featured in expensive coffee table books; fine-art tattooers are, furthermore, leading an effort to improve the image of tattooing....Fine art tattoos...appeal to an affluent, well-educated clientele...The new-style tattooee doesn't merely pick out a design from the tattooer's wall; he has an image in mind when he arrives at the studio and then discusses it with the tattooer, much as an art patron commissions a work of art. Fine-art tattoos are beautifully drawn; they reflect the Japanese influence in tattoos." [Berendt, John. "That Tattoo." Esquire, August 1989]

More information on the past and present of living art can be found in the books 100 Years of Tattoos by David McComb and 1,000 Tattoos by Riemschneider Burkhar and Henk Schiffmacher.