Biography

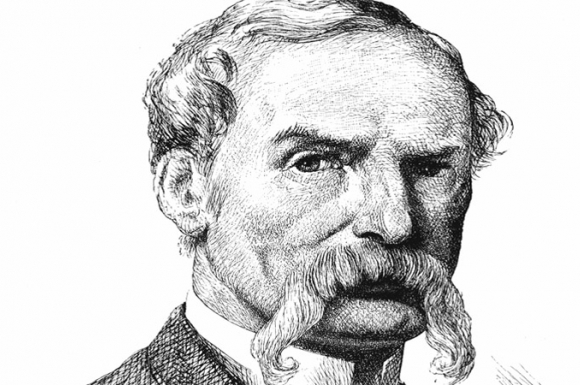

John Tenniel, one of the most recognizable Victorian illustrators, was born in London on February 28, 1820. The son of a dancer and a fencing instructor, Tenniel briefly attended the British Royal Academy before he began exhibiting his artwork. At the age of sixteen, he exhibited his first oil painting at the Society of British Artists, an impressive feat for an artist who was largely self taught.

When Tenniel was twenty, in 1840, a fencing accident with his father forced him to lose the sight in his right eye. A staunchly even tempered man, Tenniel did not react to the pain of the injury, so his father did not even know he had been harmed by his rapier. Undeterred by the partial loss of sight, Tenniel continued on his path as an artist, eventually becoming a beacon in the late nineteenth century world of illustration.

In 1850, Tenniel replaced Richard (Dicky) Doyle at Punch Magazine as a cartoonist, a position he held until 1864 when he replaced his friend John Leech as the principal cartoonist after his death. Steadfast in his routine, Tenniel would continue working at Punch Magazine until his retirement in 1901. During his career at Punch, Tenniel would produce 2,000 cartoons which inspired many famous illustrators, such as Ernest Shepard (who eventually became principal cartoonist at Punch) and Arthur Rackham (who eventually illustrated his own version of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland). In addition to cartoons, he was also known for book illustrations, such as those in The Gordian Knot by Shirley Brooks (1860), Lalla Rookh by Thomas Moore (1861, considered one of his best works), and The Ingoldsby Legends on which he collaborated with his friend, John Leech and George Cruikshank (1864).

Though Tenniel’s cartoons secured his fame to his contemporaries, it was his illustrations for Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland that truly made him a household name. Introduced to Carroll in 1864, Tenniel agreed to create forty-two illustrations after reading the manuscript. Carroll, a very particular person who took pride in his own artistic accomplishments, gave Tenniel very specific instructions concerning every aspect of the illustrations. When Tenniel completed the forty-two drafts, Carroll liked only one, the drawing of Humpty Dumpty. The relationship between Tenniel and Carroll was perpetually strained throughout the entirety of the creative process. Tenniel was upset that Carroll would not give him more freedom to execute his creative vision, and Carroll was frustrated by Tenniel’s criticism and pushback about the writing in his manuscript and the printing process. Their identical tendency towards perfectionism would not let them see eye to eye.

One of the distinctive characteristics about Tenniel’s artistic methods was that he would never draw from life. This detail set him far apart from his contemporaries, the Pre-Raphaelites, who believed that studying and drawing from nature was the only way to produce truthful art. Too much the product of academic training, Tenniel worked best when he referred to the techniques and images in his visual memory and drew without observation. This certainly worked in his favor when he argued with Carroll that the creatures in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland should not look like real animals, but should instead be fanciful creations. Carroll stated that, “Mr. Tenniel is the only artist who has drawn for me who resolutely refused to use a model and declared he no more needed one than I should need a multiplication table to work a mathematical problem.”1

The first printing of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was completed in 1865, and Tenniel took issue with the sample print sent to Carroll. Carroll had approved Clarendon Press’ printing for 2,000 copies, however Tenniel deemed it “altogether unacceptable” and insisted that Carroll cancel the print. Carroll was worried that printing would take too long and that it would no longer interest his young friends who “are all grown out of childhood so alarmingly fast.” Despite this worry, as well as the financial loss, Carroll gave the responsibility of printing to Richard Clay, a London printing house who was better equipped than Clarendon to complete the job. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was finally printed and issued in November 1865. Between 1865 and 1868, a new edition appeared every year in order to keep up with demand. A sequel was prompted by the success of the first book, and Carroll immediately asked Tenniel to illustrate Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There. Though he initially turned him down, Tenniel finally agreed to illustrate Carroll’s second book “at such time as he can find.” Through the Looking Glass was finally published, after numerous delays, in 1871. The difficult relationship between Tenniel and Carroll did not improve during the creation of the second book. It was such that Tenniel never accepted another illustration project again, and simply continued working on cartoons at Punch. He even went so far to warn Harry Furniss about his upcoming illustration work with Carroll on Sylvie and Bruno. “Lewis Carroll is impossible...I’ll give you a week, old chap; you will never put up with that fellow a day longer.”2

Tenniel lived a relatively solitary life after his wife, Julia Giani, died in 1867, two years into their marriage. He never remarried, so his mother-in-law acted as his housekeeper for twenty-three years until she died and his sister stepped in to care for him. Though flattered by the fame that his illustrations for Carroll’s two books had gained him, Tenniel viewed the work on these classics as a disruption to his routine, and immediately returned to his quiet life at home. In 1893, Tenniel was granted a knighthood for his political cartoons at Punch, as well as for his illustrations in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass.

In 1900, when Tenniel was eighty, he retired as the principal cartoonist at Punch. The eyesight in his left eye was failing due to overwork, yet he still continued to paint watercolors until he went completely blind. By the time Tenniel died on February 25, 1914, he was 93 and nearly half a century had passed since Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was published.

1. Susan E. Meyer, A Treasury of the Great Children’s Book Illustrators (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987), 68.

2. Ibid, 73.

Corryn Kosik, Walt Reed Distinguished Scholar, March 2018

Illustrations by Sir John Tenniel

Additional Resources

Bibliography

Bland, David. A History of Book Illustration. Cleveland: The World Publishing Company, 1958.

Dalby, Richard. The Golden Age of Children’s Book Illustration. London: Michael O’Mara, 1991.

Doyle, Susan, Jaleen Grove, and Whitney Sherman. History of Illustration. New York: Bloomsbury, 2018.

Meyer, Susan E. A Treasury of the Great Children’s Book Illustrators. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987.

Suriano, Gregory R. The British Pre-Raphaelite Illustrators. London: Oak Knoll, 2005.