Biography

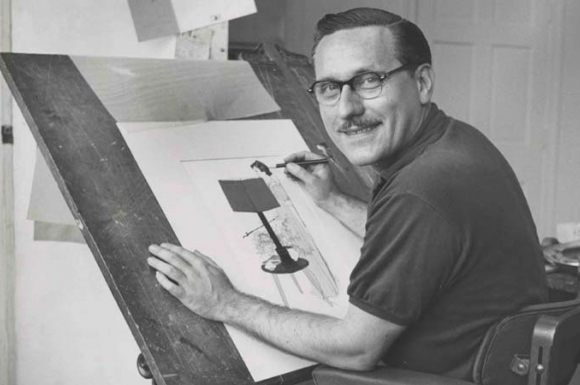

A founder of the modern glamour aesthetic, Alfred Charles Parker (1906-1985), defined the progressive look and feel of published imagery at a time of sweeping change, when Americans, emerging from the trials of economic depression and war, sought symbols of hope and redemption on the pages of our nation’s periodicals. His innovative modernist artworks created for mass-appeal women’s magazines and their advertisers captivated upwardly mobile mid-twentieth century readers, reflecting and profoundly influencing the values and aspirations of American women and their families during the post-war era.

In today’s digital information age, it is difficult to imagine the role that magazines played in a society quite different from our own, in which radio and telephone offered the only technological connection between home and the larger world. Ephemeral by design and available at low cost, Ladies’ Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, McCall’s, Woman’s Home Companion, and other leading monthlies provided a steady stream of information, entertainment, and advice to vast, loyal audiences. While top publications boasted subscriptions of two to eight million during the 1940s and 1950s, anxiously awaited journals were shared among family and friends, bringing readership even higher. Fiction and serialized novels, poetry, articles on fashion and beauty, and guidance on marriage, child rearing, and household management were staples, second only to the array of product enticements that supported the bottom line and occupied the most space in each issue.

Richly visual, mid-20th century magazines often relied upon the abilities of gifted illustrators to engage the attention and emotions of their constituents. Many artists working for publication became trusted contributors, attracting dedicated fans and attaining true celebrity status. Their ingenious, often-idealized images portrayed a compelling picture of the life that many aspired to, delineating a clear path to fulfillment and success.

Leaping beyond the constraints of traditional narrative picture making, Al Parker emerged in the 1930s to establish a vibrant visual vocabulary for the new suburban life so desired in the aftermath of the Depression and World War II. More graphic and less detailed than the paintings of the luminary Norman Rockwell, who was a contemporary and an inspiration to the artist, Parker’s stylish compositions were sought after by editors and art directors for their contemporary look and feel. “Art involves a constant metamorphosis . . . due both to the nature of the creative act and to the ineluctable march of time,” Parker said. Embraced by an eagerly romantic public who aspired to the ideals of beauty and lifestyle reflected in his art, Parker’s pictures revealed a penchant for reinvention, and his ongoing experiments with visual form kept him ahead of the curve for decades.

Born on October 16, 1906, in St. Louis, Missouri, Al Parker began his creative journey early in life, encouraged by parents with an affinity for the arts. Though their furniture business paid the bills, Parker’s father was an aspiring painter and his mother a singer and pianist. The young artist’s precocious illustrations brought song lyrics to life on the rolls of his mother’s player piano, and were proudly displayed for admiring guests. Hours spent listening to jazz in the furniture store’s record department and regular trips to the movies and theater inspired a lifelong love of music.

At the age of fifteen, Parker took up the saxophone, and by the following summer, was proficient enough to lead his own Mississippi riverboat band. Musical excursions on the Golden Eagle, Cape Girardeau, and other venerable vessels continued for five summers, “vacations with pay” that offered Parker the chance to sketch admiring fans between sets and play with jazz greats like Louis Armstrong. His first year’s tuition at the St. Louis School of Fine Arts at Washington University was financed by riverboat captain Charles J. Bender, Parker’s grandfather, who hoped to dissuade him from making music a career.

Parker played the saxophone, clarinet, and drums to fund his education, but from 1923 to 1928, he became immersed in the study of art. “Oil paint was the medium in 1924,” he recalled, but drawing was key. “At the time, [teachers] frowned on modern or abstract artists. You can always depart from the academic in figures, but you have to know how to draw well before you can do it. I learned composition and color mostly by doing.”

While in school, Parker met fellow student Evelyn Buchroeder, a gifted painter who earned but declined a scholarship to attend the Art Students League in New York City. Placing her career on hold, she remained in St. Louis, where the couple was wed in 1930. During their fifty-five year union, Evelyn was a frequent model for her husband’s illustrations and a loving mother to the Parkers’ three children.

Parker’s first professional assignment, a series of window displays for a St. Louis department store, caught the attention of Wallace Bassford, a commercial art studio head, who invited the artist to join his team of illustrators and graphic designers. Imposing deadlines underscored the speed and facility required to complete illustrations for the agency’s diverse client base, providing invaluable experience. But Parker noted that “the studio’s strange practice of signing its name to my efforts brought a frustrating tag of anonymity,” and inspired him to set out on his own. He established a business with designer Russel Viehman and rented studio space to fashion artist Janet Lane, a collaboration that would inform the dynamic compositions and stylish subject matter that Parker became known for.

In 1930, a cover contest sponsored by House Beautiful brought Parker an honorable mention and entrée into the world of national magazine publishing. The visibility of cover illustration and its viability as a lucrative outlet during the depression era, when commercial assignments grew thin, were strong incentives to make eastern contacts. “Saving model fees,” Parker said, “I posed Ev, Frances, and our coronet player’s girlfriend, dashing off three heads rendered in colored pencils.” His elegant, stylized drawings were sent to a New York artists’ representative and soon sold to Ladies’ Home Journal. Judged to be “too far out” for fiction, which tended to be accompanied by more literal representations, his art first appeared on the magazine’s fashion pages, initiating a long association with the prominent women’s monthly.

Ladies’ Home Journal editors, impressed by Parker’s creativity, began forwarding chic clothing and accessories to his St. Louis studio for rendering. Though he was not a fashion illustrator by trade, he mastered the art of “radical anatomy,” drawing “figures eight heads tall” and delineating the flow of fabric and hemlines. The artist’s first fiction manuscript came from Woman’s Home Companion in 1934, turning the tide toward the steady stream of assignments from Good Housekeeping, McCall’s, Collier’s, Cosmopolitan, American, and Pictorial Review that followed.

In 1936, Parker and his family moved to the nation’s publishing center, taking up residence on New York City’s Central Park West. Commencing a vigorous schedule of deadline-driven days, he worked at the legendary Hotel des Artistes, a gothic building that had also provided studio space to Isadora Duncan, Noel Coward, Norman Rockwell, and other celebrated creators. Lauded for his visual eclecticism and fearless experiments with media and compositional design, his popularity with editors and readers soared. Cropped compositions and extreme close-ups inspired by film, and by photography, which was a prime competitor for magazine pages at the time, made him the artist to emulate. “Al and I were more or less contemporaries and worked for . . . the same magazines, but our professional relationship might be described more accurately as master and disciple,” said glamour artist Jon Whitcomb, one of many professional illustrators who followed Parker’s artistic lead.

Despite the accolades, the path to a finished illustration “was not strewn with roses,” for “innumerable taboos abounded.” Uplifting images reflecting prevailing cultural attitudes were required and the preferences of art directors were employed as points of departure. “If one editor favored green, green predominated the palette. Red was reserved for the editor who abhorred green,” Parker observed. Publications striving to please the broadest possible audience did not often embrace invention. “An exceptionally innovating performance from the brush . . . depended to a great extent on the capacity of the art director to evoke it,” Parker said. “Once evoked, the art director expounded its merits to the magazine, which usually demanded a watered down version, innovation being reserved for failing magazines in their dying gasp for attention.”

For all of its exhilaration, life in New York was filled with unrelenting activity. Parker produced up to ten finished assignments each month and carried out the requisite social life that accompanied his success. Publishers gave “luncheons, cocktail parties and dinners . . . for their illustrators, where one could hobnob with other contributors, celebrities and VIPs, from Eleanor Roosevelt to Humphrey Bogart, whose mother was an illustrator,” he wrote. Though he enjoyed living the life that he portrayed, the artist sought a place to work that would afford more space and less distraction. In 1938, Parker and his family moved north to rural Larchmont, an easy train ride away, and rented studio space in nearby New Rochelle, a haven for illustrators since the late nineteenth century.

That year, the first of the artist’s famed mother-and-daughter covers for Ladies’ Home Journal was commissioned. Published in February 1939, his graceful silhouettes of a mother and her young daughter gliding across the ice in perfect unison and in matching outfits created a sensation. Over the course of the next thirteen years, Parker’s fair-haired cover girls celebrated holiday traditions and shared a love of sport but also played their part during World War II. Resourceful and good-natured, they modeled best behavior by rationing, sending letters abroad, and taking on dad’s chores at home and in the garden. America’s ideal family was reunited in July 1945 when Parker’s mother and daughter welcomed their returning soldier, a powerful image that inspired another narrative at the outset of the baby-boomer generation. By that December, two knitted booties—one pink and one blue—were already underway, and in 1946, a son was born.

The power of Parker’s illustrations was underscored in a 1949 Ladies’ Home Journal campaign designed to attract advertisers. Thirty of the artist’s mother-and-daughter cover illustrations were featured on a poster that read, “These cover girls really started something! Since their introduction in 1939, American women have been adopting them, copying their clothes, flooding us with letters—making them ‘part of the family.’ Mother and daughter sparked a fashion trend that sprang from Journal covers to stores across the country. They demonstrate Journal power to put personalities (and products) into American marts and homes.”

The origins of Parker’s mother-and-daughter series was explained toward the end of its life span in a 1951 letter from Ladies’ Home Journal editor Bruce Gould to Richard S. Chenault, art editor of The American Magazine. “Al Parker’s famous Mother and Daughter covers grew out of the fact that Mrs. Gould and I used to skate on Sunday afternoon in Princeton at Baker’s Rink. Since neither of us skate very well, we had plenty of time to watch those who did. One thing particularly attracted our attention. Mothers who were very good skaters themselves . . . were teaching their little daughters and taking more pride in their daughters’ progress than in their own undisputed prowess. This spectacle of the proud mother and aspiring daughter seemed to us to have cover possibilities,” he wrote.

Gould and his wife, Beatrice Blackmar Gould, who was also a Ladies’ Home Journal editor, communicated their concept to Parker, who began experiments on the theme. After several tries, he eliminated distracting backgrounds in favor of a clean poster design that emphasized strong, simple forms and recognizable narratives. “After that, everything was easy,” Gould said. “Seventh Avenue saw a good idea and mothers and daughters throughout the United States have been wearing similar costumes, similar jewelry, et cetera, et cetera, since.”

Al Parker’s last mother-and-daughter cover was published in May 1952. His idyllic portrayal of an officer’s joyful return to his still-beautiful wife and growing family during the Korean War conflict brought an era of the artist’s career, and the magazine’s history, to a close. Ladies’ Home Journal’s covers were solely photographic after that, completing the transition away from traditional narrative illustration that had begun in the latter part of the previous decade. Photography captured the moment for many publications that were striving to remain current, ultimately relegating the art of illustration to a more decorative or conceptual function.

Parker and his family lived in Westport, Connecticut, from 1940 to 1955, where his studio, surrounded by “cornfields and crickets,” was in close proximity to a community of noted magazine illustrators who made the town their home. There, he maintained his focus on editorial and advertising assignments but also made time for music. During World War II, Parker became the drummer in a jazz band populated by instrument-playing members of New York’s Society of Illustrators, including cartoonist Cliff Sterrett, illustrator Ken Thompson, and art directors Clark Agnew and Paul Smith. Performances in hospitals and on bases were punctuated by drawing sessions that produced cast inscriptions and personal portraits as mementos. Parker’s celebrity appearances and donations of original art inspired the sale of war bonds, raising substantial subsidies for the war effort.

Though he graciously offered advice to aspiring professionals throughout his career, in 1948, Parker became a founding member of the Institute of Commercial Art in Westport. This popular correspondence course initiated by Albert Dorne became better known as the Famous Artists School, and boasted a celebrated faculty that featured illustrators Norman Rockwell, Stevan Dohanos, Robert Fawcett, Ben Stahl, Harold von Schmidt, Austin Briggs, Jon Whitcomb, Peter Helck, Fred Ludekens, and John Atherton. “Their belief is that anyone with the time and desire can master the craftsmanship of art,” wrote Arthur D. Morse in a 1950 article for Collier’s. “They agree that the inner flame which inspires great art is the inherent personal property of the individual.”

Though the tenets of draftsmanship and design were carefully documented in his curriculum, Parker’s inexhaustible quest to find new visual solutions could not be taught. Continuing his experiments, the artist made magazine history by creating illustrations for five fiction articles in the September 1954 issue of Cosmopolitan magazine, each under a pen name in a different artistic style. “Change is a style in itself,” Parker said. “Developing an approach and then dropping it in favor of something fresh is a completely calculated move on my part.”

By the late 1950s, magazine publishing had undergone substantial change inspired by a trend toward suburban living that reduced newsstand sales, making women’s periodicals less appealing to advertisers. Rising production and circulation costs produced shrinking profit margins and television became the media of choice for information and entertainment. To combat this trend, a range of creative marketing techniques were employed. Geographically specialized and split editions allowed manufacturers to test advertisements by reaching segmented markets. Striking graphics, product samples, and foldouts engaged audiences but could not stem the tide that would ultimately create less opportunity for artists, and even Parker was not immune. By the end of the 1960s, illustration-friendly publications like The Woman’s Home Companion, Collier’s, and The Saturday Evening Post had ceased publication, and many others had changed course.

Parker and others found some relief on the pages of magazines like Sports Illustrated and Fortune, which continued to reserve space for expressive entries by artists. Sports Illustrated invited him to capture the excitement of premier auto racing at the Monaco Grand Prix for its readers, a highlight of his career. Painting and photographing on location with little editorial oversight, he produced a masterful suite of paintings that spread across eight pages of the May 11, 1964 issue. Experiential and documentary, this vibrant visual essay conveys a true sense of local color and an intimate glimpse of both racers and spectators.

As Westport grew more crowded, Parker, who suffered from asthma, sought a change of climate and went west. In 1955, the Parker family lived briefly in Scottsdale, Arizona, where he was “knee deep in American Airlines ad art,” but finally settled in Carmel Valley, California, where he continued to work and to play music until his death in 1985. Sought after as a speaker by arts organizations and schools throughout the United States, Parker exhibited his work and received the highest professional honors for his contributions to the field. In 1965, he was elected to the Society of Illustrators’ Hall of Fame, an award bestowed to him by legendary illustrator Arthur William Brown. Honorary doctorate degrees from the Rhode Island School of Design and the California College of Arts and Crafts in 1978 and 1979, respectively, were sources of pride for the artist.

Frank Eltonhead, a gifted art director who worked with Parker at Ladies’ Home Journal and Cosmopolitan, reflected on his accomplishments. “Perhaps once in an art director’s lifetime a person will enter the field of illustration with a viewpoint and talent so individual, so strong, and so right . . . that in a comparatively short time this person’s feeling and thinking and work has affected the thinking and work of his contemporaries.” Parker’s influence ran deep, and his vibrant images, borne of diverse methodologies and aesthetic approaches, inspired and entertained millions who encountered his art at the turn of a page.

Stephanie Haboush Plunkett, Deputy Director/Chief Curator, Norman Rockwell Museum

Illustrations by Alfred Charles Parker

Additional Resources

- Yesterday’s Papers

- “The Illustrator in America, 1860-2000,” by Walt Reed

- Museum of American Illustration at the Society of Illustrators

- The Society of Illustrators

Bibliography

Auad, Manuel, Stephanie Haboush Plunkett, and David Apatoff. Al Parker: Illustrator, Innovator. San Francisco, CA: Auad Publishing, 2014.

Plunkett, Stephanie Haboush and Magdalen Livesey. Drawing Lessons from the Famous Artists School: Classic Techniques and Expert Tips from the Golden Age of Illustration. Beverly, MA: Rockport Publishers, 2017.

Plunkett, Stephanie Haboush. Ephemeral Beauty: Al Parker and the American Women's Magazine, 1940-1960. Stockbridge, MA: Norman Rockwell Museum, 2007.

Reed, Walt. The Illustrator in America, 1860-2000. New York: Society of Illustrators, 2001.

_1_60_60_c1.jpg)