Description

Early Origins

Political or editorial cartooning is based on caricatures, a technique dating back to Leonardo da Vinci’s sketches. William Hogarth (1697-1764) has been attributed with the early development of political cartoons. In 1732, A Harlot’s Progress, one of his “Modern Morale Series” engravings, was published. His pictures combined social criticism with a strong moralizing element, and targeted the corruption of early 18th century British politics. In the 1750s during a military campaign in Canada, George Townshend (1724-1807), 1st Marquess Townshend produced some of the first overtly political cartoons. He would circulate his ridiculing caricatures of his commander James Wolfe among the troops.

William Hogarth, A Harlot's Progress

James Gillray (1756-1815), considered the father of political cartooning, directed his satires against Britain's King George III, depicting him as a exaggerated buffoon, and Napoleon and the French people during the French Revolution. The political climate of Gillray’s time was favorable to the growth of this art form. The party warfare between the Loyalists and Reformists was carried out using party sponsored satirical propaganda prints. Gillray's incomparable wit, keen sense of farce, and artistic ability made him extremely popular as a cartoonist.

George Cruikshank (1792-1878) was from a family of caricaturists and artists. At an early age he learned the techniques of etching, watercolor, and sketching. He gained success when in 1811, he drew a series of political caricatures for The Scrounge, a Monthly Expositor of Imposture and Folly. Cruikshank’s style was very similar to Gillray’s. Cruikshank was fond of satirizing British political parties and the prince. When the prince became King George IV, he unsuccessfully tried to suppress satirists and their publishers with bribes.

The Illustrated Magazine

A number of humorous magazines were started in France and Britain. The most famous periodical was Punch. Founded in 1841 by journalist Henry Mayhew and engraver Ebenezer Landells, this weekly publication was renowned for its wit and irreverence. In 1843, the magazine introduced the term "cartoon," which referred to comic drawings. John Tenniel, the chief cartoonist for Punch, was the most prolific and influential cartoonist of the 1850s and 1860s, and perfected the art of physical caricature and representation. Some of Punch’s other cartoonists include John Leech, George du Maurier, and Charles Keene.

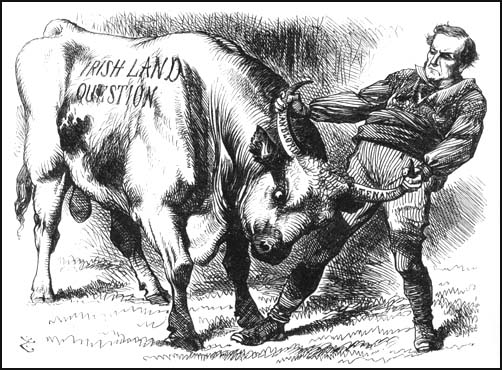

John Tenniel, Irish Land Question

By the mid-19th century, major political newspapers in many countries featured cartoons designed to express the publisher's opinion on the politics of the day. In the United States, Thomas Nast (1840-1902) landed an illustration job at Harper’s Weekly. Nast satirized the major political issues of his era: slavery, the Civil War, Reconstruction, and corruption. Nast was most famous for his editorial cartoons drawing attention to the criminal activities of William Marcy “Boss” Tweed's political machine in New York City. Eventually, Tweed was forced to flee the country to avoid prosecution. Nast was also responsible for the association the donkey and elephant as symbols for the Democratic and Republican parties.

Modern Times

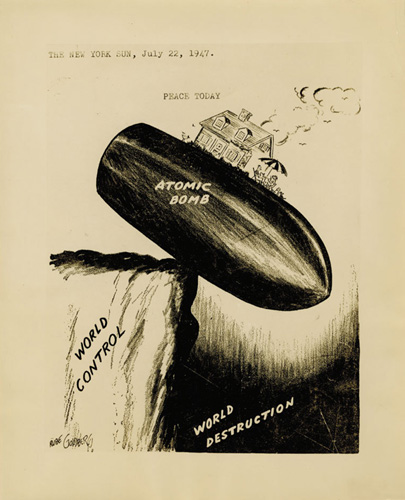

Political cartoons can usually be found on the editorial page of many newspapers, although a few are sometimes placed on the regular comic strip page. Most cartoonists use visual metaphors and caricatures to address complicated political situations, and thus sum up a current event with a humorous or emotional picture. Rube Goldberg (1883-1970) began his editorial cartooning for The New York Sun in 1938, and was soon syndicated nationally. Using strong visual metaphor, his political cartoon, Peace Today, published on July 22, 1947 won the Pulitzer Prize. Others rely on a text-heavy style, like Pulitzer Prize winner Garry Trudeau’s Doonesbury, which tells a linear story, usually in comic strip format.

Rube Goldberg, Peace Today

_60_60_c1.jpg)

_60_60_c1.jpg)

_60_60_c1.jpg)

_60_60_c1.jpg)